Ever heard of “space junk”? The term is a broad one, but it often refers to the remnants of space stations, rocket and satellite missions floating in space. This detritus is currently orbiting the Earth at incredibly high speeds, with junk within 800 to 36,000 kilometers of Earth reaching velocities of up to 17,500 mph. At this speed, even a small piece of flaking paint is enough to considerably damage the window of a rocket or space station. On the other hand, the size of a golf ball can destroy an entire satellite due to the force of an impact.

According to NASA, more than 500,000 pieces of space debris currently orbit the Earth, with that number on the rise. These bits of debris, which are at least as big as a marble, pose an increasing risk to research projects, satellites and space missions. The question of how space debris can be disposed of is therefore not only a matter for NASA, but also for most nation states and modern companies. After all, without satellites the Earth’s telecommunications apparatus would cease to exist as we know it.

A common central idea for “cleaning up” space usually involves bringing the garbage back to Earth, where it would burn up due to the enormous heat built up on re-entry. Now a number of different countries around the world have developed different strategies that could make this process a practical reality.

USA: Brane Craft brings space debris back to Earth

Last year, the US non-profit organisation Aerospace Corporation received NASA’s second round of funding for its “Brane Craft” project, which could soon enter the implementation phase. Brane Craft is an extremely thin, but extremely resistant, bullet-proof spacecraft. The object, which is designed to look a bit like a piece of colourful foil, is sent into the stratosphere, where it then wraps around individual parts of the space debris. It then navigates back towards Earth, burning up along with the debris on the way.

To keep technology and processes cost-effective, the paper-thin spaceship is powered by ultra-thin solar cells and a very small amount of additional fuel. In addition, the ‘mother ship’ which sends the film into space would be able to send out a consistently high number of Branes – which is made possible due to the light and thin structure of the technology.

Japan: Hooking the junk out of space

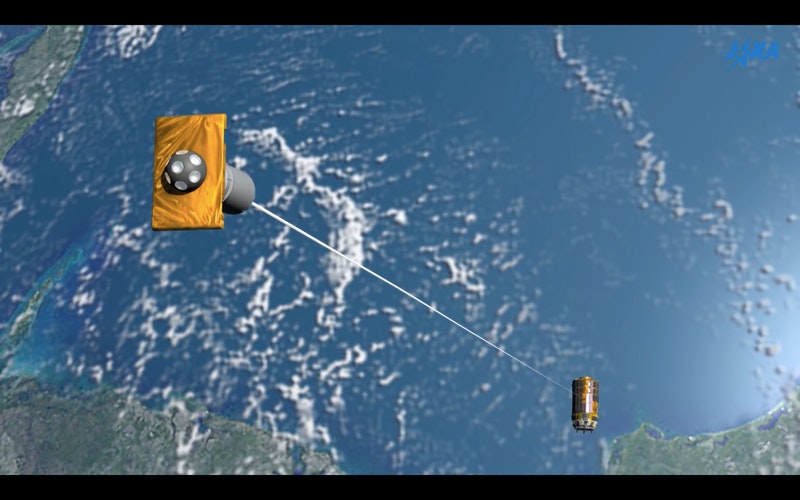

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency has also developed its own idea for how to bring down space debris. As part of the Kounotori Integrated Tether Experiment (KITE), it aims to grab large pieces of space debris using an oversized hook. The whole operation would also require a specially developed space craft, which pulls the hook, together with scrap, back through the atmosphere. Unfortunately, this fully functional space vehicle would also have to burn up as a result of the fall towards Earth, meaning the effort and costs per removal would be extremely high and only viable for the largest and most dangerous pieces of space debris.

Germany: Space junk? Shoot it down with lasers!

At the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), they want to kill two birds with one stone: first the DLR plans to employ high-frequency laser pulses to better locate individual pieces of space debris and determine their movement and trajectory. In a second step, the junk is then shot with the laser so that they slow down and are deflected into the Earth’s atmosphere. According to DLR, however, it may be several years before the system is fully developed.

England: RemoveDebris harpoons space debris

As part of the “RemoveDebris” experiment, the Surrey Space Centre in England is testing a similar strategy to Japan. Instead of a hook though, their method would use a harpoon and net to snare the junk before conducting a controlled crash into the atmosphere. So far, the project is still in the early test phase and does not capture any real space debris – instead it hunts down small satellites that the system itself emits.

These are just some of the technologies that could help remove dangerous space debris from our orbit. It’s still not known which of the ideas will become reality and enter into actual production, although in the end it is likely to come down to balance sheets. The head of the RemoveDebris project, Guglielmo Aglietti, summed up the issue with the BBC, stating:

“In my opinion, whether or not there are going to be real missions to remove debris will depend on cost. And I worry that if they are extremely expensive, people will think about other priorities.”

This article is a translation by Mark Newton of the original article by Laura Wagener which first appeared on RESET’s German language site.