In 2022, it was still unusual for the citizens of Germany to be asked to save water. However, forecasts, such as the OECD’s Environmental Outlook for 2050 have been pointing out for years that water scarcity will become a problem worldwide without political countermeasures. In addition to setting and adhering to climate targets, it is the way we deal with water that has to change.

Worldwide, between 30 and 45 percent of treated fresh water is lost through burst and leaking pipes. Supply systems for fresh water can be very complex, particularly in the more population-dense areas. In Berlin, for example, treated water is transported via a network of pipes and pipelines that together are about 7,800 kilometres long — over 17,000 if we add sewers. If water leaks at any point, finding the weak spot is difficult.

The use of sensors that check water pressure in real time, immediately reporting any malfunctions, would be one way to stem this water loss. But how critical is the loss of fresh water?

Some countries lose up to 40 percent of treated fresh water

Worldwide, the share of “non-revenue water”, water that has been produced and is “lost” before it reaches the customer, is between 30 and 45 percent. However, the International Water Association (IWA) includes not only water losses due to real leaks but also apparent losses such as theft and measurement inaccuracies in this term, as well as water provided free of charge, for example for firefighting.

While the proportion of non-revenue water, or NRW for short, in Germany is between five and ten percent, depending on the source, other countries fare much worse. In both Norway and Croatia, for example, over 30 percent is lost in the public drinking water network. In Uganda and Italy it is even over 40 percent. England recorded losses of about one trillion litres of water due to leaking pipes in 2021 alone, according to the Guardian.

And, according to water scarcity forecasts, such losses may simply no longer be compensated for by a surplus of fresh water in the future.

With water loss comes scarcity

In the coming years, more and more people will suffer from water scarcity. The causes are manifold, but are mainly made up of global warming, population growth and water pollution and overuse. While the demand for water, which is already barely sufficient in many regions, continues to rise, the availability of clean drinking water is decreasing all over the world.

Dry and particularly hot regions, such as aforementioned Uganda and Italy are particularly affected. German soils have also lost a total amount of water over the last 20 years, that’s roughly equivalent to the volume of Lake Constance.

Losing water through leaks in supply systems is also associated with a higher environmental impact, as it not only causes consequential damage to resource-intensive infrastructure but also seeps into wastewater collection basins or into the ground. Recovery is then costly and increases the water supply’s carbon footprint.

Detecting leaks in water pipes early – the Pydro “PT1

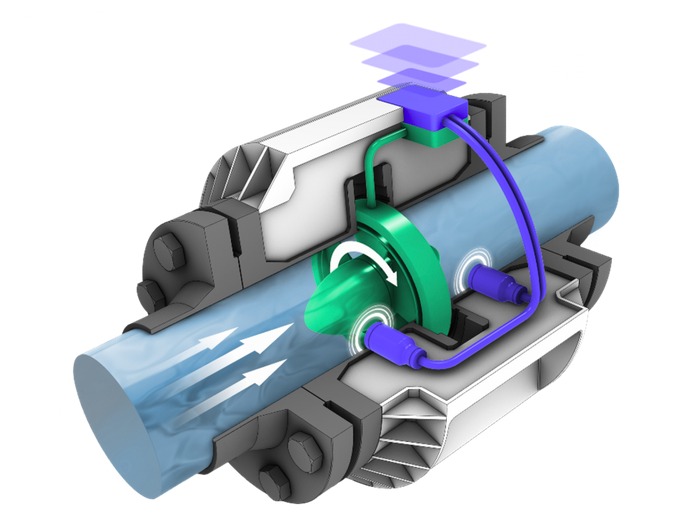

German start-up Pydro shows how networked sensors for detecting leaks in water pipes work. With the “PT1“, it has developed a flow meter for water pipes that can supply itself with energy – and is already available on the market.

The meter, which is installed as a connector between two water pipes, is equipped with a ring propeller for this purpose. The water pressure in the pipes sets it in motion, which in turn causes the PT1 to draw current. According to the manufacturer, a low resistance is sufficient to supply sensors and transmission electronics with power. For the water circuit, this means only a small pressure loss of 0.2 bar.

The PT1 transmits the collected data to a server in real time via a mobile network. Pydro offers the monitoring of water networks as a service, including corresponding software and troubleshooting. As soon as an unusual drop in water pressure is detected, network operators can react immediately and precisely.

Energy self-sufficiency is also possible for countries with low levels of electrification

The fact that Pydros flowmeters generate their own electricity also solves the problem of decentralised monitoring systems. In order to ensure far-reaching monitoring, the sensors must also be able to be used in locations that are kilometres away from the power network. While energy supply is less of a problem in urban areas, Pydro’s monitoring system brings the necessary independence from the power grid in rural regions or in countries with a low level of electrification. In addition to increased flexibility, the sensors also ensure monitoring during blackouts or prolonged power outages.

In future products, Pydro also wants to use its flow meters to control the flow of water. As Pydro founder Mulundu Sichone revealed in an interview for Frankfurter Runschau, this would reduce the load on water pipes. For water to be available as soon as the tap is turned on, as it is in Germany, there must be sufficient pressure in the pipes. The required overpressure at peak consumption times is one of the main reasons why leaks and damage occur in the first place.

“Letting something foreign into one’s system always involves dangers”.

Pydro has already been able to win important partners for the development of the PT1, including the German Federal Foundation for the Environment, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy and the European Union. In addition, Pydro is one of 40 companies selected by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology to fight water scarcity in 2022.

The distribution of the Pydro PT1 is expected to increase to 8,200 systems by 2025, but many utilities in the founding country Germany are still reluctant. At the beginning of last year, Pydro’s sensor network system was only used in Gelsenkirchen.

So, why are our water pipes not yet equipped with modern sensors?

Press spokesperson of Berlin water utility company Berliner Wasserbetriebe, Astrid Hackenesch-Rump, justified this in an interview with RESET. She says that the losses of fresh water in Berlin and in Germany are already very low. In the capital, only three percent of fresh water is lost in burst pipes and leaks. Accordingly, the strategy for maintaining Berlin’s water network was already functioning sufficiently reliably.

Instead of sophisticated sensor technology, the previous strategy was based on empirical values about the materials used, past repairs and planned modernisation measures. Taking into account external influences such as the traffic volume over the lines, the network could also be reliably maintained using the current systems.

Moreover, upgrading existing lines with new sensors is not harmless. Installing something “foreign” in a safe system increases the risk of damage and contamination. Overall, the risk is too high to make it worthwhile to further optimise the already low losses.

Losses may no longer be offset by surplus in the future

Real-time monitoring of our water supply is therefore not the only way to deal with fresh water sufficiently without losses. However, Berliner Wasserbetriebe’s strategy is based on data that has been meticulously recorded for many decades.

On the other hand, the water losses in other countries show very clearly that the leak detection systems used are unreliable everywhere. So new technologies could certainly be put to good use here.

The evaluation of the lost water as “non-revenue” also makes it clear that the loss of water is mainly discussed as a financial loss. Water utilities can easily pass this on to citizens through their pricing. Thus, there is insufficient financial pressure to minimise water losses.

The urgency of reducing freshwater losses with monitoring systems like the PT1 must therefore be discussed at the political level. While the lost water can currently still be compensated by surplus, this will almost certainly no longer be possible in many parts of the world in just a few years.

The potential of such technologies is great enough for this. According to Pydro founder Mulundu Sichone, decentralised monitoring in the water supply could save 13.5 billion litres of water and 27 million kilowatt hours of energy per day worldwide.