Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow) is a small town in Alaska, at the northernmost tip of the United States. Its 4000-strong population rely on fishing in the Arctic Ocean as part of their food source. But in recent years, fish stocks aren’t what they used to be. Locals have begun finding wild Alaskan salmon along with their usual catches. Delicious, yes. But why are they appearing at all?

Every year, winter sea ice melts and leaves a cold pool (a stretch of very cold water) near the seafloor in the Arctic Ocean. The cold pool is a boundary that keeps Arctic species separate from sub-Arctic species. But climate change means the sea is warmer, ice is receding and the cold pool isn’t forming as it should. Predators are swimming further north and disrupting the usual food chains. And salmon are appearing in Utqiagvik, a sure sign that something is amiss with the Arctic Ocean.

AI modelling could be the solution the Arctic Ocean needs

“The future isn’t behaving like the past,” Leslie Canavera explains to RESET from her home in Virginia. Canavera is CEO and Co-Founder of PolArctic, a Startup that’s using AI modelling techniques to create a digital twin of the Arctic. She describes how indigenous communities used to be able to predict how ice in the Arctic would behave and knew the knock-on effects upon their fish stocks. While in 1990, 82 percent of fish stocks in the Arctic were at biologically sustainable levels, this number dropped to 65 percent by 2019, according to the FAO. “A lot of practices that people have relied upon and understood to be true [are no longer applicable],” Canavera continues. “Not having that baseline is really challenging going forward.”

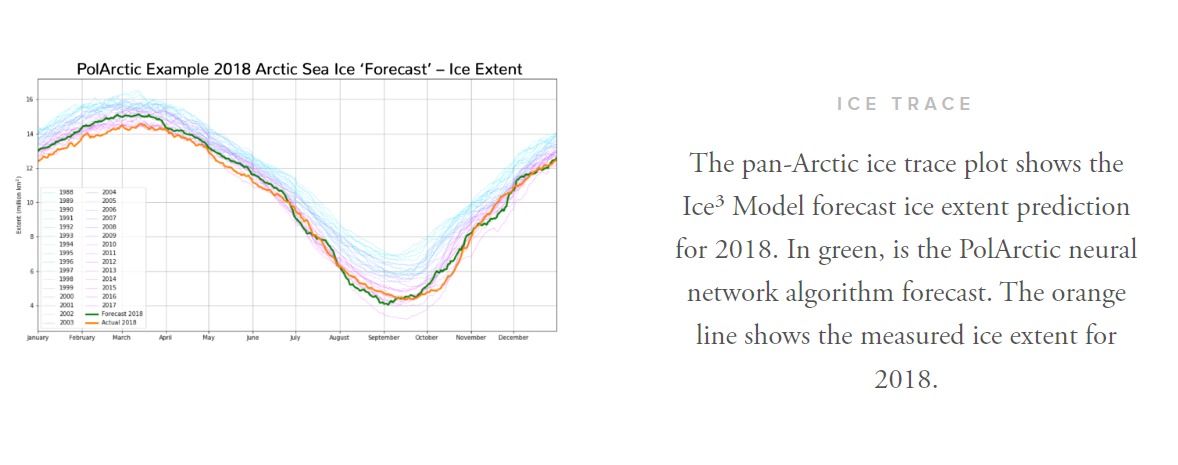

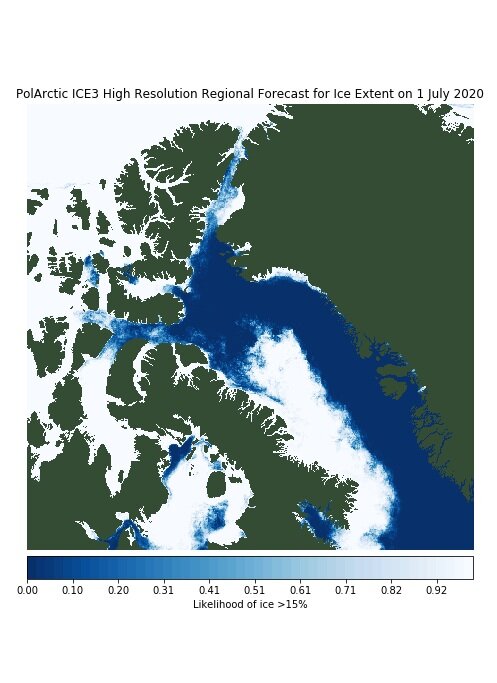

PolArctic is co-founded by Canavera and Lauren Decker, both Alaska Natives. They use artificial intelligence and machine learning to map out and predict changes in the Arctic Ocean, providing fishing and shipping industries alike with the information they need to adapt to climate change in the region. Previous models of the Arctic use statistical modelling techniques. But this relies upon the assumption that the Arctic will continue to behave as it always has, not accounting for the elephant in the room: climate change is melting ice in the Arctic at alarming rates. PolArctic’s AI-based modelling techniques use historical data too, but are also able to learn systems and trends, forecasting climate impacts on the Arctic much more accurately.

The data that PolArctic uses to train its models doesn’t only come from Western science, but also from the indigenous knowledge of local communities in the region. Canavera wrote for the WWF that “AI and indigenous culture are often positioned as if in conflict with each other,” but explains how the success of PolArctic’s projects would not be possible “without the benefits of both.” With an estimated 370 million indigenous people whose livelihoods are negatively affected by climate change, collaborative solutions are urgently needed to help these communities survive.

The digital twin advises on what to fish in the Arctic

PolArctic is nearly 18 months into its latest project: mapping out a digital twin of the Arctic. They aim to release it to industries in January 2025. But how exactly do you begin replicating the Arctic Ocean’s 14 million square kilometres, with over 240 fish species and diverse marine life? Canavera gives us an insight. PolArctic uses an agent-based modelling technique, programming each fish as an agent with all their varied characteristics. Simultaneously, the region’s landscape is mapped out in great detail.

Then, it gets interesting: the model is able to give advice, such as “fish school A, not school B, because school B needs to grow to ensure the biodiversity of fish stocks,” Canavera says. “You can then start asking the model questions,” she continues. “What if the ice doesn’t reach the same region next year?” The information the digital twin provides can help fishing industries adapt and boost profits, all while increasing the amount of fish in the Arctic despite the effects of climate change.

Communities and industry alike eagerly anticipate the model

Although they are thousands of kilometres away from one another, the Arctic Ocean and Europe are intrinsically linked. Pressure systems that keep cool air in the Arctic and warm air in the south are being disrupted by climate change, leading to the heat waves, cold spells and extreme weather that are becoming increasingly commonplace in Europe. Meanwhile, microplastics from as far away as France have been found in the Arctic Ocean, highlighting the long-term effects that our growing amount of waste has on the planet as a whole.

Despite this, PolArctic’s digital twin offers hope that the Arctic may be able to adapt to the effects of climate change. Canavera relays the excitement of both indigenous communities and the fishing industry, who are eagerly anticipating the launch of the digital twin. In the words of Canavera, “our model has the potential to be game changing.”