Content to: research

Starting From Scratch: ‘Basic Data’ Buoy Bolsters Marine Protection

Successful marine protection needs a strong scientific basis of sound data. A floating measuring station in the Baltic Sea aims to provide this.

New Breakthroughs in Nuclear Fusion Announced – But How Clean is Fusion Power?

Fusion power is still some decades away, although new strides are being made every year. But how does fusion compare with nuclear fission power?

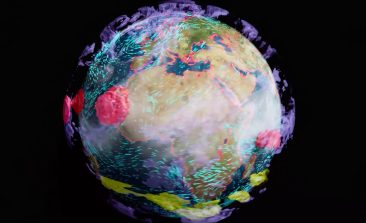

Can Video Game Hardware Help Climate Research? Nvidia to Create a ‘Digital Twin’ of Earth

The manufacturer of graphics cards wants to use its know-how to recreate the Earth in a digital simulation on a unprecedented one metre scale.

Zooniverse: A Million Volunteers are Helping to Spot Animals, Transcribe Records and Weather Watch in the Name of Science

Whether its counting penguins, deciphering historical records or listening to the stars, Zooniverse harnesses people power to assist in breaking down the big data behind scientific research.

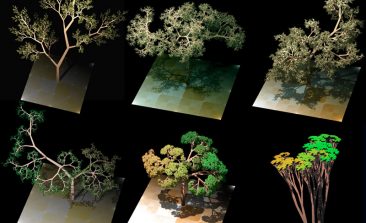

Interview: How Can We Make AI More Environmentally Friendly?

What potential does artificial intelligence have to help us protect the environment and tackle climate change? And with all the computing power it requires, how can we make artificial intelligence itself more environmentally friendly? What can companies, developers and governments do to ensure AI helps us protect - and not destroy - the environment? We put our questions to Stephan Richter from the Institute for Innovation and Technology.

The BCFN YES! Research Grant Competition Deadline Is Fast Approaching

The Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition's YES! competition is for PhD and post doc researchers who are looking to improve the sustainability of our food system. A 20,000 EUR research grant for one year is up for grabs.