Although carbon dioxide often grabs the headlines, it’s not the only greenhouse gas capable of damaging our environment. In fact, pound for pound, it’s not even the worst.

For example, although it makes up far less of our atmosphere then carbon dioxide, it absorbs thermal radiation much more efficiency and therefore has a global warming potential (GWP) around 86 times stronger than CO2 per unit mass. Overall, carbon dioxide likely has a bigger impact since much more of it is released, with methane accounting for around 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Regardless, experts suggest removing methane – a valuable product in its own right – could still contribute to cooling the environment, or at the very least slow its rate of warming.

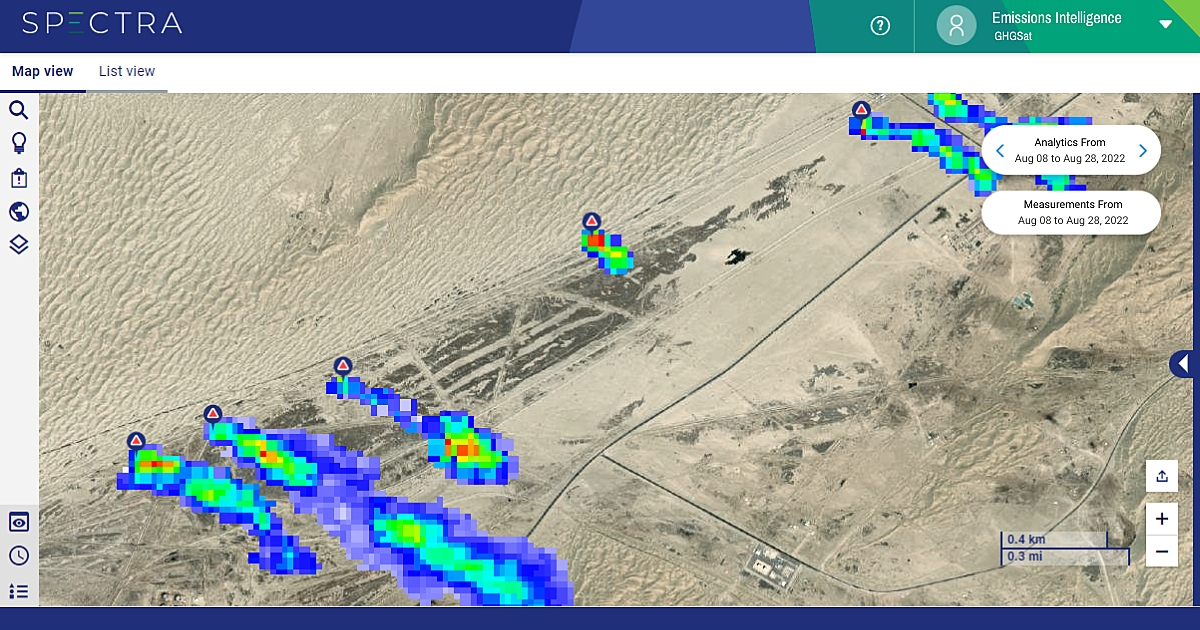

To highlight this fact, business experts Bloomberg are publishing daily images of methane leaks across the world during the ongoing COP27 summit. To achieve this, they have teamed up with GHGSat, an organisation using satellites to monitor methane leaks around the globe.

GHGSat uses a patented imaging interferometer to detect methane with orbiting satellites 500 kilometres above the Earth’s surface. Usually, these sensors can spot methane through the distortion of sunlight as it reflects back out to space. Methane blocks part of the light spectrum, which can then be detected by sensitive sensors. Although other corporations are conducting similar work, GHGSat suggests their images are of the highest resolution, and they are the only commercial methane monitoring organisation which can attribute leaks to specific facilities, although the ESAÄs Sentinel-5P programme is also capable of this accuracy.

In addition to satellite-based sensors, GHGSat has also developed sensors for aerial surveying from aircraft, allowing for even more accurate readings. All of this is available to organisations via SPECTRA, a data platform with a recently announced premium subscription service.

Using this technology, GHGSat and Bloomberg have been publishing exclusive images showing methane leaks from different sources and different nations. So far, this has included methane from the following sources:

- Decomposition of organic waste in a Canadian landfill (1,185 kilograms per hour)

- Methane pumped out of a Polish coal mine (3,410 kilograms per hour)

- Methane leaking from an Iranian fossil fuel facility (795 kilograms per hour)

- Methane pumped from a US coal mine (440.4 kilograms per hour)

- Decomposition of waste in an Indian landfill (1,328 kilograms per hour)

- Methane emissions from six Chinese oilfields (4,477 kilograms per hour)

- Emissions from a Turkmenistan oil and gas field (8,501 kilograms per hour)

- Methane gas released from a Pakistani landfill (1,403 kilograms per hour)

Landfills in particular are notable sources of methane and provide an almost constant stream of the gas. The gas originates from the decomposition of organic material, like food scraps, breaking down in the absence of oxygen and, according to Bloomberg, accounts for 20 percent of all methane emissions.

Coal mines are another important source, especially in China. When coal is extracted, gas methane is often encountered and this must be vented to prevent buildups and potential explosions. Usually, these mines do not have the facilities or experience to capture the useful gas as a secondary product, so it is simply released into the atmosphere.

In both cases, gas capture systems could be implemented to not only reduce emissions, but also potentially create additional revenue streams.

Overall, the biggest producers of methane are China, the United States, Russia, India, Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Mexico. These eighth countries make up around 50 percent of all methane emissions.

By exposing this environmentally damaging and wasteful process in daily images, hopefully the full scale of methane emissions can be exposed, and more attention brought to reducing or capturing the dangerous gases.

At the time of writing (November 13th), we are currently mid-way through the COP27 climate conference being held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. The conference follows on from commitments made in the Paris Agreement of 2015, although progress on these issues is difficult to gauge. Only 24 of 193 have submitted their carbon reduction plans to the UN.

This year, the major conversation points are discussing how new technologies, renewable energy sources and management practices can mitigate emissions, and how Global North nations can help those in the Global South adapt their economies. As always, financing these climate positive changes will also be discussed, as will the impact of the ongoing war in Ukraine.