Last week came the news that Google is ‘winding down’ work on Project Loon, an ambitious, multi-year project which aimed to spread internet access across the globe via high-altitude, self-navigating balloons.

The venture, supported by Google’s parent company Alphabet and developed at the firm’s X Labs, originally launched in 2013 and appeared to be on track to reach its goal. However, on January 22nd 2021, Loon chief executive Alastair Westgarth released a statement suggesting the company had had difficulty in making the concept economically viable:

“While we’ve found a number of willing partners along the way, we haven’t found a way to get the costs low enough to build a long-term, sustainable business.”

The aim of Project Loon had always seemed hugely ambitious. Vast tennis court-sized balloons would float on the edge of the stratosphere and beam down internet connections to rural and underserved areas. Loon envisioned a network of dozens, if not hundreds, of balloons circumnavigating the globe using their own onboard suite of advanced navigation and wind predicting software. It was claimed each balloon, which could travel as high as 12 kilometres above sea level, would cover a 5,000 kilometre square area with a viable 4G connection, connecting offline communities to the world wide web.

The latest significant update from the project was when Loon teamed up with Kenyan Telkom to provide 4G balloon internet across remote parts of the country. In order to do this at scale, Loon had also developed mobile ‘autolaunchers’ which could deploy a balloon every 30 minutes to rapidly build and maintain a network. The official launch of the collaboration was, years behind schedule, in mid-2020, when a fleet of around 35 separate flight vehicles began serving an almost 50,000 square kilometre area of western and central Kenya. Despite the end of official Google support for the project, Loon will continue to serve its Kenyan contract until March 2021, as well as provide 10 million USD for developing additional infrastructure.

Unfortunately for Loon, although several telecommunication companies and government agencies were interested in their concept, as the CEO explained in his official statement, the biggest challenge was that Loon wasn’t looking to connect the next billion users, but instead “has been chasing the hardest problem of all in connectivity — the last billion users”.

According to a report from the GSM Association, over the last decade, mobile internet availability rose from 75 percent of the world to 93 percent. This doesn’t mean that 93% of people are actually using the internet that’s available to them, of course. There are still other barriers in place, that balloons and other connectivity providers, can’t solve: the fact that the 3 or 4G mobile phones required are prohibitively expensive, the internet doesn’t provide enough content in their own language, or maybe that people haven’t been equipped with the right skills to use digital devices.

The project also received criticism from elsewhere. To some, the balloons were simply drones by another name and built on pre-existing concerns about Google’s role in global surveillance. Others suggested it would essentially create digital monopolies in certain regions as well as place important infrastructure in the hands of potentially fickle multinationals.

That is not to say the Loon concept is not without utility, however. In fact, one of its greatest success stories was not in bringing internet connectivity to far-flung rural communities, but in providing assistance during environmental crises. In 2017, it deployed its balloons to aid rescuers and civilians caught up in flooding in Peru, and to bring connectivity to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. It might be in this sector that Google’s technology might find the most utility and broader acceptance, especially when used by government agencies operating outside of a business model.

The years spent chasing this balloon adventure also weren’t completely in vain, the company assures us. Some of the technical solutions developed for the balloons are going to be used to help develop other projects. Just recently, in December 2020, Loon engineers published a paper in Nature describing how their technology had pioneered new deep learning techniques that they were using to help their balloons autonomously form networks in the challenging conditions found at those altitudes. While another Loon breakthrough—sending high-speed data via pulses of light – is already being used in a separate X project, Taara, which is also designed to bring internet connectivity to underserved regions.

LEO satellites & solar-powered routers: other technologies step up to close the digital divide

Project Loon was only one approach to spreading internet access into rural areas – and several other technologies have emerged over the past few years. One which has attracted a large amount of attention is Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite internet. In June 2020 Elon Musk’s SpaceX launched 58 satellites into low earth orbit as part of the Starlink programme, which aims to provide satellite internet via thousands of small satellites working in combination with transceivers on the ground. Because these types of satellites are closer to earth, they are able to provide internet connections with less lag than traditional satellite internet. Downsides include the fact that satellites decay in orbit and need to be regularly replaced, and the fact that right now at least, they can only handle a certain amount of traffic.

The much-debated, ultra-fast wireless technology 5G has also been touted as a solution. Especially in the wake of the coronavirus, which saw so many schools switch to online formats, it has been suggested that 5G technology could radically transform remote learning systems on the African continent, improving the quality of learning thanks to its faster speeds and enabling students in remote locations to participate in classes in real time.

TV white space technology, while it hasn’t received as much attention as 5G and LEO satellites, is another tech solution already being tested in Microsoft’s Airband Initiative, which was launched in the summer of 2017 and aims to reach 3 million Americans in rural areas who don’t have broadband with connectivity by July 2022. White space internet uses a part of the radio spectrum known as ‘white spaces’, a frequency range that is created when there are gaps between television channels. However it’s still unclear what kind of connectivity TV white space internet will be able to provide. The speeds may be comparable to 4G cellular internet, which likely will turn out not be sufficient in the long term.

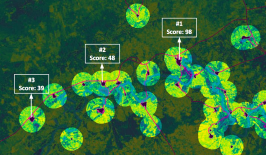

However, when it comes to meaningfully solving the digital divide in rural areas, perhaps for now it is lower-tech solutions using wired internet that provide the most accessible opportunities for people in rural areas to fully take advantage of the promise of the internet when it comes to learning, working, healthcare, and quality of life. Some approaches include We! Hub (picture aboved) which offers a centralised, solar-powered public internet access point and BRCK, specialised hardware routers that can supply Wi-Fi even without a steady power supply. While other innovations, such as Farmerline in Ghana, provide some of the same crucial information that the internet can provide, but instead using pre-existing SMS networks.

Not only are these projects often developed in conjunction with local telecommunication partners, but they are also built to match the needs and demands of specific communities.

That’s not to say the Loon balloon approach has been completely abandoned. A similar concept is currently under development by Altaeros, which uses aerostats to spread internet connectivity over a 60 kilometre radius. Unlike Project Loon’s high altitude balloons, Altaeros’ balloons are tethered to the ground and operate on a more local scale. The last significant news on this project came in 2019, with testing of their so-called SuperTowers. Time will tell if Altaeros can make the concept more economical and desirable than Google.

This article was co-authored by Marisa Pettit.