For farmers on Indonesia’s Sumbawa Island, nature has always traditionally kept them informed about weather cycles and patterns. For generations, farmers have looked to the tamarind and kapok trees to predict rainfall and plan the sowing of their seeds. However, climate change is throwing off these natural rhythms as well as the traditional knowledge that depends on them, potentially ruining crops and livelihoods.

To solve this issue, a collaboration of international agencies have developed a weather prediction app specifically tailored to the needs of Indonesia’s farmers. However, the effort does not simply end there. The team, including the Bandung Institute of Technology, USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance and international development nonprofit World Neighbors, understands creating the app is only one – and arguably the most simple – part of the solution. Farmers, some of them in remote areas, also need to understand and trust the new technological approach.

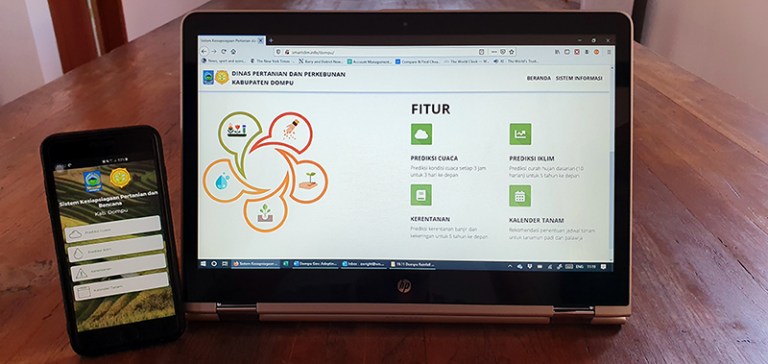

The app is the brainchild of Dr. Armi Susandi, an Indonesian lecturer at the Bandung Institute with extensive experience in developing early warning and smart agriculture applications. Using meteorological information, local historical data and annual yields, the app provides rainfall, wind speed, humidity and air pressure predictions for the local area, as well as recommendations for which crops to grow. In extreme situations, it can also provide advance warning of coming hydrometeorological disasters. The app can provide short term predictions, updating the next three days’ forecast every three hours, and monthly predictions for as much as five years in the future. For the many sloped dryland farms of Indonesia’s Dompu Regency, knowing when and how much rain is going to fall is essential to farming success.

But there are immediate challenges to the uptake of the new app. Firstly, there is the fact that only around 45 percent of Indonesian farmers have access to a smartphone – with most of those being younger farmers. Even those with a smartphone, may have limitations in terms of signals. But perhaps the most salient issue is the natural reticence of traditional smallholder farmers to adopt and rely on unfamiliar technology. After their initial workshops, around 60 percent of farmers agreed to use the technology. Although a significant figure, it also illustrated that many were not yet ready to hitch their livelihoods to a mobile phone application.

In an interview with Inhabitat, Edd Wrights, World Neighbors’ regional director for Southeast Asia, explained the steps being taken to solve these problems. The most significant development is the creation of local agricultural extension workers. These are specially trained locals who accompany the NGOs to educate and familiarise the farmers with the technology. In cases where the farmer does not own a smartphone, they can also provide access or give them offline analog copies of the apps’ coming predictions.

Importantly, the new technology is not simply thrust upon them. Farmers are taken through a step-by-step education process in which traditional methods, climate change and the technology behind the predictions are all discussed. This hopefully creates an environment where traditional and modern methods are brought together and not seen as in competition. In the final stage, farmers are shown how to implement the models and develop comparative assessments of yields between those who used the rainfall predictions and those who did not.

It is hoped that adoption amongst some leading members of the farming communities will help greatly increase trust in the app overall. It seems to be working. After reluctant farmers saw the success of early adopters, more agreed to join a trial of the app. Now around 3,700 farmers in 36 communities are trained in the use of the app.

Currently, the app is being trailed largely in select areas of Dompu, but now World Neighbors hope to expand it further to the regions’ 200,000 inhabitants in 81 villages. Although face-to-face workshops have been instrumental in kickstarting adoption, World Neighbors also understands continuing this process on a large scale would be prohibitive in terms of time and cost. To this end, there are endeavouring to fully digitalise the training experience and make it available online.

This is not the first time Indonesia’s farmers have been given some digital support in their farming careers. Previously, RESET has written about another digital app, Dr. Tania, which helps farmers identify pests and disease amongst their crops.