A Peruvian programme is using drones to help put urban settlements on the map (quite literally), in a bid to improve housing rights and climate change resilience for underserved local residents.

The growing use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), otherwise known as drones, has led to a large number of industries and organisations adopting the technology. And it’s also given rise to debates about whether their benefits outweigh the significant ethical and legal concerns – particularly when it comes to questions of surveillance and privacy.

But we’ve also seen multiple examples of drones used “for good”, including in delivery, information sharing and disaster relief. We’ve seen floating drones that clear trash out of waterways, drones that plant trees in Spain and mangroves in Myanmar, and even drones that are able to locate hidden landmines.

More recently, drones have also been employed in the fight against the coronavirus, to encourage social distancing in several countries such as the U.S., Spain, the U.A.E., and India and to deliver medical supplies in China.

They’ve also become an important tool for spatial data collection and for surveying and monitoring land use. In urban areas, drones have been found to be especially useful as a tool for mapping and “legitimising” informal settlements. Aerial photos taken by drones have an advantage over satellite imagery because drones can fly at lower altitudes and capture higher quality images to pick up on accurate details like the exact size of different families’ plots of land, and the small pathways that are characteristic to dense informal settlements.

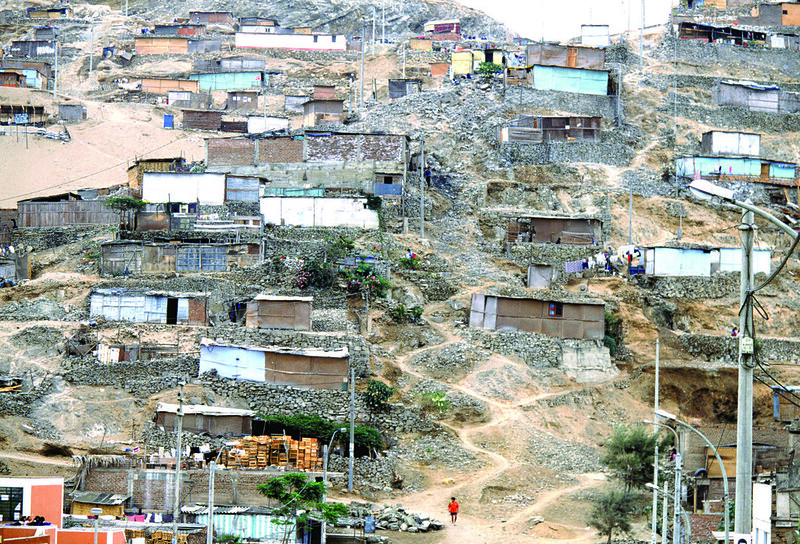

Throughout the world, informal settlements, often otherwise known as slums, are defined by inadequate water and sanitation systems, insufficient living space, and a lack of land and housing rights. Using drones to map these kinds of informal areas can help to resolve several issues in slums that render slum dwellers vulnerable. For example, using drones in a land registration process helps to identify and assign numbers to plots and the families occupying the plots, so as to formalise ownership and grant housing rights. Furthermore, the high quality images that drones provide, including the “tilt shift” feature, allow for 3D-modelling which can be helpful when planning infrastructure improvements like installing drainage systems to prevent floods.

Drones Set to Map Urban Settlements in Peru

In January 2020, an 80-million US dollar joint project between the World Bank and the Peruvian Agency for the Formalization of Informal Property (COFOPRI) was approved to use drones to update the Peruvian urban cadaster. Cadasters are public registries of land use that help authorities to better plan and manage urban growth and spatial distribution. The aim of the project is to design natural disaster and extreme weather defenses, provide urban services in informal neighborhoods and improve their urban planning for sustainability and inclusivity. The Vice Minister of Housing and Urbanism of Peru has stated that 4.8 million people will benefit from this project.

Twenty-two municipalities in the provinces of Lima, Chiclayo, Lambayeque and Piura will participate in the project and benefit from the updated geospatial information. As Peru is a highly urbanised country (nearly 80% of the population lives in urban areas) with a large informal settlement population where the urban poor are marginalised, mapping settlements in this way has the potential for huge impact. Formalising squatter settlements not only offers improved security for the residents by allowing them the right to occupy that space, but also allows municipalities to collect property tax – an important source of revenue which can be used towards improving local services in the city. Peru has one of the lowest rates of property tax collection in the Latin American region, which could be because only 8 of Peru’s 522 urban municipalities have complete and updated cadasters (!) – at least according to this project document. Consequently, Peruvian municipalities are lacking the financial resources they need to provide basic services, invest in city infrastructure, improve the quality of life and ensure their cities’ resilience to climate change and natural disasters in the future.

In order for urban land registers like this to be useful, they have to be updated frequently, so the project also has a focus on building municipal capacity to keep them up to date. Through mapping, governments also have the opportunity to engage citizens as partners in urban planning and make the spatial data open source and available for citizen use. In recent years, informal settlement maps in several cities have been made available to citizens through open source geospatial data platforms such as Quantum GIS (GIS stands for Geographic Information Systems). Furthermore, some mapping programmes train locals to operate the drones so that they are involved as partners in the data collection process. Participatory and open source mapping was applied in Kenya and Uganda with UN-Habitat. Open Mumbai is another example of participatory planning and community mapping of the slums of Mumbai, India. While the WeRobotics Flying Labs network is training people throughout the Global South to increase existing expertise in drones among local populations and accelerate the positive impact of local aid, health, development and environmental solutions.Updated cadasters have also proven to assist in natural disaster relief and reconstruction, as was the case in Ecuador when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake destroyed parts of the city of Portoviejo in 2016. Authorities used drone footage from before and after the earthquake to identify the families who needed relief. Further successful cases of the use of drones for land mapping have come from Kenya, Fiji, and Albania.