Hardly any sector works without platforms. Companies sell their goods on e-commerce marketplaces and much of the collaboration within and between companies is organised via cloud services and other digital interfaces. It is no different in agriculture today. On more and more farms, digital platforms are taking over the organisation of operations and the distribution of products. As in many other areas, the services of large corporations are far ahead. Farmers pay for this with their data.

Examples such as LiteFarm show that there is another way. This open-source platform was developed from the ground up and is specifically tailored to the needs of sustainable farmers.

Platforms in agriculture

Platforms take on many tasks in agricultural businesses. Cloud platforms, for example, enable communication between the machines used in the fields and stables. They also provide an important infrastructure for the further processing and utilisation of the collected data. Digital marketplaces and e-commerce platforms are another type of platform. They can be used to sell agricultural products and inputs between producers, processors and traders.

At the same time, digital marketplaces are also being used to sell agricultural products to end consumers. However, the proportion of food sold online is not yet particularly high. It accounted for 7.2 percent of grocery sales worldwide in 2021.

Sharing and rental platforms for machines in the production sector, on the other hand, are well established. The co-operative machinery rings that have existed since the 1960s have long since arrived in the digital world.

In agriculture, there are also platforms that manage access to data. The Rhineland-Palatinate GeoBox is a publicly owned alternative. It allows farms to store data in a decentralised manner and share it with other farms.

At a national level, the BMEL is establishing an agricultural master platform and the Federal Ministry of Economics is developing the public data infrastructure Agri-Gaia.

Farm Management Information Systems (FMIS) are another type of platform. In a study conducted by the University of Göttingen in 2019, 55 percent of the farmers surveyed stated that they already use FMIS. In contrast, a survey conducted by the Bavarian State Research Centre for Agriculture (LfL) in the same year found that around a third of farmers use FMIS. The difference could be due to the fact that the first study was an online survey and therefore probably reached more tech-savvy farmers. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that the prevalence of FMIS is already significantly higher today.

Managing operations digitally with FMIS

Agricultural businesses are not only confronted with a multitude of information and regulations, but the amount of data is also growing. Every sensor, every new machine or software used in the fields and stables provides additional data. All of this needs to be managed. Digital management tools are designed to make work easier and simpler for farmers.

FMIS can cover all of the farmer’s tasks and bring them together in one place – from field mapping and operational planning and documentation of production to monitoring and evaluating field work, resource utilisation, crop development and weather and growing conditions. To create a rich data context, sensors and other IoT-based technologies can also be integrated into many of the FMIS.

However, it is not only the production processes that can be organised more easily via FMIS, but also the administration of the business. Accounting, personnel management and compliance with quality standards and regulatory guidelines can be integrated into them. Suppliers, processing companies, wholesalers and consulting, insurance or financial service providers are also sometimes connected to the platforms. The 365FarmNet platform, for example, offers consulting services from external experts.

Decision Support Systems (DSS)

A further development of FMIS are Decision Support Systems (DSS), which also use simulations and algorithms, for example to model the water use efficiency of plants or nutrient availability. However, these are not (yet) widely used.

FMIS should thus relieve farmers of a lot of work and simplify processes. In addition, the consolidation of data also has the potential to enable processes to be planned in line with requirements and, in the best case, to be organised more efficiently.

Big business for big players

The platforms are predominantly provided by start-ups, multinational tech companies and food and agricultural groups. The companies are by no means acting altruistically. According to a study by the IÖW, many agricultural companies link the use of their products such as pesticides, seeds or fertilisers to the use of digital management platforms. What they get in return is data. This is intended to help the companies to further develop their products. But there is something else at stake, namely the better marketing of other products. Digital services are used to bind users to a specific provider ecosystem. Once here, they are encouraged to buy other agricultural products from the provider, as Kevin Cussen from LiteFarm reports.

“However, this can also create lock-in effects for customers, for example if the use of products is not possible without the use of the associated platform or if farm management platforms are only tailored to certain cultivation systems or varieties and thus set strong incentives for the use of the products of the respective agricultural company,” the authors of the study also note.

Only a few FMIS pay attention to sustainability – even if the opportunity is there. Using less fertiliser or water, for example, can save money as well as having sustainable “side effects”. But there are alternatives. LiteFarm, for example, is a free open-source platform that not only focuses on data sovereignty but also aims to achieve sustainable agriculture.

LiteFarm: Software development by farmers for farmers

The LiteFarm platform was developed from a collaboration of farmers, researchers, designers, software experts and open source enthusiasts and is independent and free of charge. The stated goal is to meet farmers where they are and equip them with the tools they need to make informed and responsible decisions for the health of their farm, their livelihood, their community and the planet.

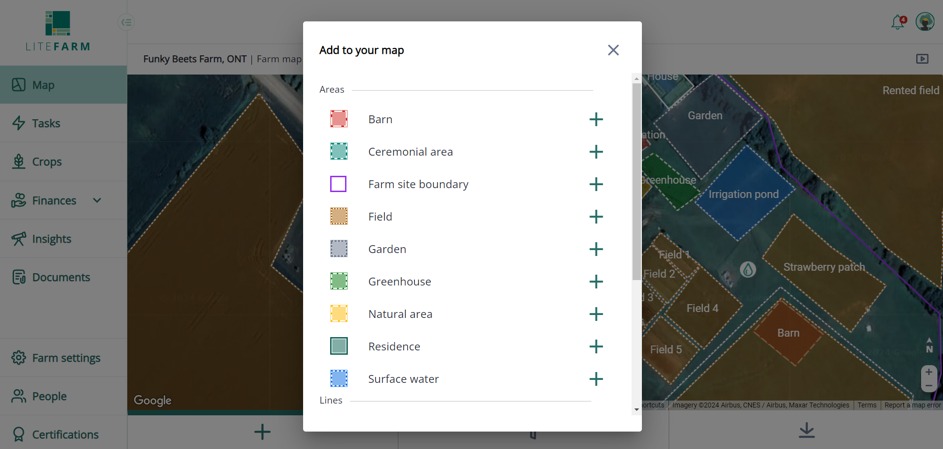

As with commercial FMIS, farmers can enter, assign and complete all tasks directly via the LiteFarm app. Detailed area maps can also be created and the status of the cultivated areas is displayed. However, the functions are specifically tailored to the needs of organic farmers.

One of the most important pillars for improving sustainability is diversification, says Kevin Cussen. “This means that when we develop a new feature, we think about how a user would experience that feature on a diversified farm. Your farm could have greenhouses, fields, pastures, buffer zones and wooded areas on multiple plots. Dozens of crops could be grown in some of these areas, and they could serve as grazing areas for numerous different species of animals. Areas where crops and livestock are not being raised still provide other forms of beneficial or environmental services that impact the farm.” LiteFarm endeavours to make its management system both reflect the complexity of sustainable farms and make interaction with the platform as intuitive as possible.

LiteFarm also has a large catalogue of plants. It currently contains 375 crops. In addition, users can add to the plant catalogue themselves and indicate whether they would like to share the crop with the wider LiteFarm community when creating it. “Since the end of 2023, when this ‘nomination’ feature was introduced, users have contributed more than 385 plants to our community catalogue,” reports Cussen. “Our goal is to work with regional allies who will review these nominations and give the green light for inclusion in the general data set for users in that region.”

With open source to an app for everyone

However, developing a tool that is attractive to users all over the world and at the same time tailored to the regions with their specific requirements is not easy. “The truth is that it’s almost impossible to find a balance when a tool is used in more than 150 countries,” says Cussen. “But we also believe that this problem lends itself well to open source. Our development process involves a broad group of farmers from four continents to ensure that we receive regular feedback on our developments. We also develop open-ended features whenever possible so that users can customise LiteFarm to their needs and we can learn from their adaptations.”

LiteFarm is currently working on integrating the rearing of animals into the application. In order to offer the best possible support, all tasks that have been created by farmers over the years are being analysed. The first prototype has already been built, and now the community is being asked to provide feedback for optimisation. Users can also indicate their priorities for further development.

The users’ data is used exclusively for non-commercial research projects on sustainable agriculture in anonymised form. As part of one of these research projects, a standardised method is to be developed to measure the impact of organic farming systems. To this end, the participating farms collect the data using the LiteFarm app.

Agriculture is facing major challenges: On the one hand, it is severely impacted by biodiversity loss and the effects of climate change. On the other, agriculture itself massively contributes to these issues.How can digital solutions on fields and farms help to protect species, soil and the climate?

We present solutions for a digital-ecological transformation towards sustainable agriculture. Find out more.

How can digital solutions on fields and farms help to protect species, soil and the climate?

We present solutions for a digital-ecological transformation towards sustainable agriculture. Find out more.

LiteFarm supports with certification

LiteFarm also provides support with certification. In order to prove that their plants are grown according to organic principles, farmers must provide extensive records and documentation. This makes the process leading up to organic certification very labour-intensive. This can be a significant obstacle, especially for small farmers. To make the process easier, LiteFarm creates organic certification documents based on the information that producers generate on the platform. Farmers can then share these with the certification bodies.

According to its own information, LiteFarm is already being used on more than 4,700 farms in over 155 countries. “The features are developed by a core team paid for by grants and donations, in collaboration with a community of volunteers who contribute,” says Kevin Cussen.

LiteFarm is a project of the University of British Columbia. The project is also a member of the OpenTEAM consortium, which is committed to improving soil health and promoting the development of solutions for climate change.

Giving FMIS the right framework

Many scientific studies agree that endless fields planted with monocultures are not the way forward for sustainable agriculture. It is much more important to promote small-scale, more diverse agriculture. Species-rich fields are more robust against pests and better able to withstand the weather extremes that are increasing with climate change. But to achieve this, the development and use of field robots, sensors and FMIS must be geared towards diverse crops. In any case, LiteFarm has already come a long way along this path.

In order for other suppliers to follow suit, appropriate incentives must be set at a political level. This includes defining resource conservation, soil health and species protection as agricultural goals. This will encourage manufacturers to integrate these aspects into their technologies.

It is also important to create clear legal requirements that guarantee farmers’ ownership of data and data sovereignty. This ensures transparency, security and fairness between farmers and technology providers. At the same time, geodata, weather data, satellite data and other data relevant to agriculture should be publicly accessible. Some federal states such as Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg have already implemented exemplary concepts for the provision of public geodata, for example with the “MapRLP” geoportal. In conjunction with appropriate funding, this can facilitate further open-source applications.