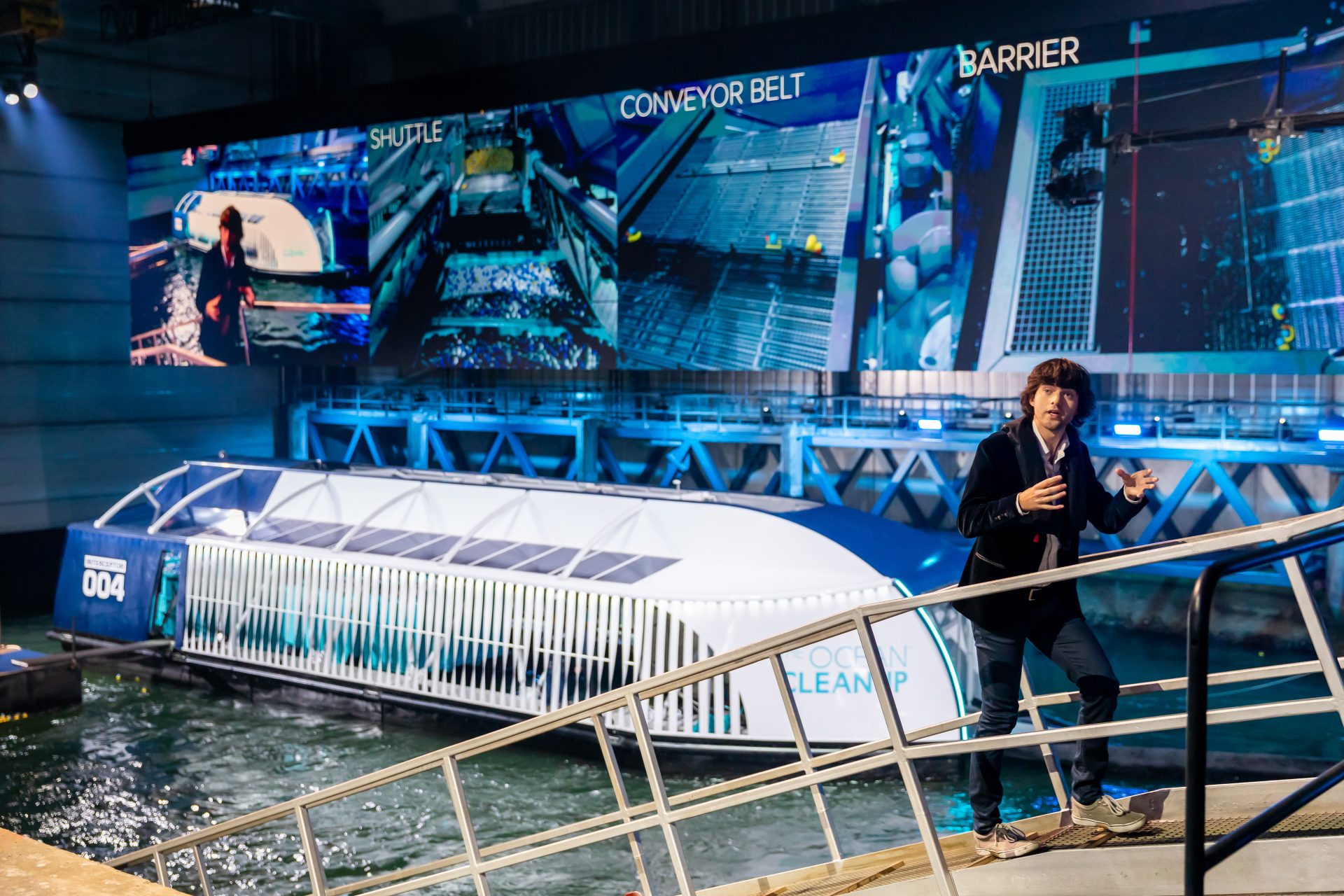

We’ve written several times about the ambitious projects devised by Boyan Slat, a young Dutchman who developed the plan of using a giant floating barrier to catch plastic in the Pacific Ocean where a huge garbage patch has developed. However, the latest news wasn’t good. The prototype system, consisting of an arched tubular construction designed to catch the plastic waste at sea with the help of natural oceanic forces, recently failed under real conditions. But Slat doesn’t give up that easily. Now, his organisation is aiming to tackle the problem at the root. He has now developed a ship-like Interceptor which can collect waste on its journey into our seas and oceans by patrolling the heavily polluted rivers of the world. Earlier this week, Slat revealed the Interceptor waste collector to the public for the first time in the port of Rotterdam.

How does the Interceptor work?

According to Slat, the Interceptor – a 24-metre-long waste collector – has been in development for around four years. It is powered by solar and can autonomously collect plastic waste from rivers without the need for recharging or downtime.

The aim is to place Interceptors at strategically important parts of the river system, where they will be able to collect plastic waste floating on the water surface between two barriers. One barrier is located on one side of the river; when a piece of floating plastic runs into it, it is directed towards the opposite bank. There again, a little further downstream, a second barrier is located, which then guides the plastic into the actual collection device – a kind of ship pointing upstream at the end of the second barrier. The collected plastic is then transferred to a container via a conveyor belt. It is hoped this system will capture the vast majority of plastic on a river, without impeding or obstructing other ships. Once the container is full, the ship automatically sends a message to The Ocean Cleanup for emptying.

The next big solution?

Large amounts of plastic waste travel to our seas and oceans via rivers, so the potential of the Interceptor shouldn’t be underestimated. Two years ago, researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research Leipzig (UFZ) and the Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences calculated in a study that the ten river systems with the highest plastic load (the amount of plastic transported in water) are responsible for around 90 percent of the global plastic input from rivers into the sea. Most of these are located in Asia, with the Yangtze (China), the Indus (Pakistan) and the Yellow River (China) leading the way. “If we succeed in halving the plastic input from the catchment areas of these rivers in the future, a great deal would already have been achieved,” says Dr. Christian Schmidt, hydrogeologist at the UFZ. Collecting the plastic within limited river sections consisting of bottlenecks is also much easier than fishing it out of the open sea – especially as the majority of the plastic in our oceans has already partially decomposed and is floating below the surface.

However, marine plastic is not only washed into the oceans by rivers and can also enter them via coastal cities, fishing boats or from airborne plastic. So even if they are used on all ten major polluting rivers, the Interceptors cannot expect to completely tackle all of the sources of the plastic that ends up in our oceans, let alone solve the problem of plastic parts already floating in the sea. Nevertheless, “cleaning” up the rivers like this a helpful approach.

How realistic is the whole thing?

Even though Boyan Slat presented the first prototype a few days ago, the new waste collection system is still in the test phase. Two Interceptors are currently floating along two heavily polluted rivers in Indonesia and Malaysia, while two river waste collectors in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam and in Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) are due to go into operation soon. Another Interceptor is also planned to enter a river near Bangkok (Thailand).

According to Slat, a single Interceptor can collect around 50,000 kilos of plastic waste every day – perhaps even 100,000 kilos under optimal conditions. Considering the huge amount of plastic carried by large rivers, a large number of collection stations will be needed in order for the Interceptors to have meaningful impact. The price of this kind of high-tech equipment of course also an important factor. And what happens to the plastic after it is collected? Only professional disposal would ensure that the practically indestructible pieces of plastic don’t end up in the same cycle and make their way into the ocean again. In fact, that is part of the problem. Much of this plastic enters the rivers in the first place because there are no well-functioning recycling systems to be found in the densely-populated areas on the banks of those rivers. It is not only a problem for the countries where these plastic-clogged rivers are found. China, for example, has long been an international dumping ground for unwanted plastic, including from nations in Western Europe and elsewhere.

This clearly shows that plastic pollution is a global problem that we all contribute to – and which we must solve together. The first and most important step must be to produce less plastic overall. In that regard, we as consumers are just as much in control and responsible as plastic manufacturers and politicians. We also need to significantly increase global recycling quotas so that fewer plastics end up in seas and oceans in the first place. However, until that happens, technologies such as the Interceptor could play an important part in ensuring that our rivers and seas contain more fish than pieces of plastic, at least for the time being.

This is a translation by Mark Newton of an original article that first appeared on RESET’s German-language site.