The old adage often states bigger is better – and that often seemed to hold true for manufacturing. Since the industrial revolution, manufacturing has been increasingly centralised into larger and larger factories and complexes, which often churn out consumer objects regardless of the immediate demand for them. It’s a system that led to the creation of many vast communities across the world, and has generally served industrialists well – especially in terms of their bank accounts. Unfortunately, it did Mother Nature less favours.

The centralisation of industry into large factories not only had immediate local environmental impacts, such as the air pollution and degradation of groundwater, but also contributed hugely to global carbon emissions, with manufacturing alone providing around 30 percent of global CO2.

Now, entrepreneurs and innovators are experimenting with new ways of doing things. The combination of renewable energy technologies, artificial intelligence and automation means microfactories are now becoming a reality. One project in New York is now experimenting with a means of promoting the concept, and reusing plastic waste at the same time.

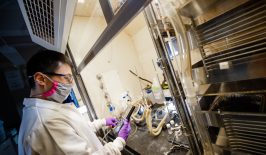

Circular Economy Manufacturing is a team of engineers and designers who have been exploring ways of plugging microfactories into an off-grid, circular economy. They have developed a shipping container-sized microfactory which can shred and reconstitute plastic waste without any toxins, pollutants and waste.

The concept works like this. A large solar array on the roof of the container uses the Sun’s energy to charge a bank of batteries. These in turn power a range of tools required to recycle plastic. However, as a microfactory, the process has been cut down to only the absolutely necessary processes. First, plastic waste purchased from a nearby recycling center is passed through a shredder until it is broken down to tiny flakes. These flakes are then moved into an innovative rotational heat mould. In contrast to larger recycling plants, only the actual mould itself is heated, making the process more energy efficient. The result is a small hollow plastic ball known as a ‘GI globe’. The researchers are also working to develop a range of other moulds for other objects.

Generally speaking, this portable recycling microfactory has largely been developed as an exhibition piece for the public to visit. Its location of Governor’s Island is not exactly conducive to practicality – as garbage must be shipped to it across the water – but the team hopes it will educate locals about the possibility of microfactories. Such small recycling plants could play a vital role in establishing a circular, more sustainable consumer economy.

Smaller is Better?

Whereas some manufacturing enterprises are going big – looking at you Elon Musk – for others the future is much more compact. The microfactory concept started to emerge in the 1990s, especially as manufacturing equipment itself was scaled down and miniaturised. Now they form an innovative, if still largely theoretical, avenue in manufacturing which could have beneficial side effects for the environment.

Advocates point out that the smaller floor space of microfactories – which can be reduced to the size of a shipping container – means they cut down on costs and emissions. The use of automated technology and artificial intelligence, also means microfactories can essentially run themselves with minimal human involvement, reducing heating, lighting and other energy demands. The larger an industrial complex becomes, the more energy is likely to be wasted on superfluous processes. In a microfactory, energy use is more efficiently directed only to the specific processes that require it.

Furthermore, microfactories could in theory be placed all over the nation closer to their customers. This means logistics, raw materials and manufacturing no longer needs to be concentrated in single, large locales and emissions from long haul supply and deliveries can also be reduced. By spreading the manufacturing capacity over a wider area, could also help diminish the local environmental damage of large industrial complexes. A network of microfactories could theoretically only produce goods for the immediate metropolitan area they serve.

Microfactories could also respond more flexibly to consumer demands. Instead of producing a large number of products and then marketing them to customers, microfactories could be connected to the internet and directly respond to incoming orders from the local area. This means microfactories will only produce products when there is an actual demand for them, cutting down on waste and further cheapening the process for small scale manufacturers.

The low cost of microfactories is particularly revolutionary. Setting up manufacturing plants can now cost thousands, not millions of dollars. With their much lower start-up costs, microfactories are now within the budget of local cooperatives, initiatives or businesses. Microfactories could be made available on a ‘microfactories-as-a-service’ model, meaning manufacturers can rent the equipment only for the time that they need it. This could hugely contribute towards a more local, circular and hopefully sustainable consumer economy that responds more efficiently to customer demand.

The modular, customisable nature of microfactories also allows them to be expanded and reduce in response to economic conditions, while they can also be set up in pre-existing infrastructure, such as old industrial warehouses. Ultimately, they could produce a huge range of products, from small 3D-printed items, to entire electric vehicles. One e-vehicle manufacturer, Arrival, is already using microfactories – albeit slightly larger ones – to produce electric buses.

There are of course, some downsides to microfactories. More microfactories does mean more supply routes, which may overall increase emissions from supply and deliveries. It is hoped the shorter length of these routes, especially in regards to delivering final products, may compensate for this, while the use of drones and other automated vehicles has been suggested as a solution.

There is also the issue of unemployment – long associated with increased automation of the manufacturing process. Microfactories only need to hire a handful of people, and most of these will be in more technical support roles. The proliferation of multiple microfactories around the country can mitigate this, but for major industrial towns based around large manufacturers, the microfactory concept could sound like its deathknell.