As the world’s population continues to grow, so too does the pressure on a wide range of factors. Water, food and power are major areas of concern, but so too is the need for housing. In many cases, especially in the Global South, cement and concrete are the go to solution for growing city populations and sprawling urbanisation.

For many elsewhere, cement is already a familiar, oft lamented, sight. Frequently seen as the hallmark of poorly planned high occupancy housing estates or post-war communist regimes, cement is the primary ingredient in creating our ‘concrete jungles’. And while psychologists and sociologists debate the societal and psychological impact of concrete, one issue is much clearer: it’s effect on the environment.

The production of cement is environmentally concerning for two main reasons. Firstly, the process requires high levels of heat, which in turn results in high energy demands. Secondly, the process of calcination – in which limestone is heated to produce so-called clinker – also results in carbon dioxide as a waste product. Up to around 60 percent of cement’s carbon footprint results from this process alone, while the global cement industry is responsible for around eight percent of all emissions. Furthermore, according to the IEA, the direct CO2 intensity of cement production increased 1.8 percent per year between 2015-2020. Alternatively, 3 percent annual declines are required to reach a 2030 Net Zero Emissions scenario.

To reach this lofty goal, the IEA suggests both new blended types of cement, which use less clinker, and innovative technologies should be used. The Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS), in conjunction with the Heriot-Watt University, has been conducting studies into just that.

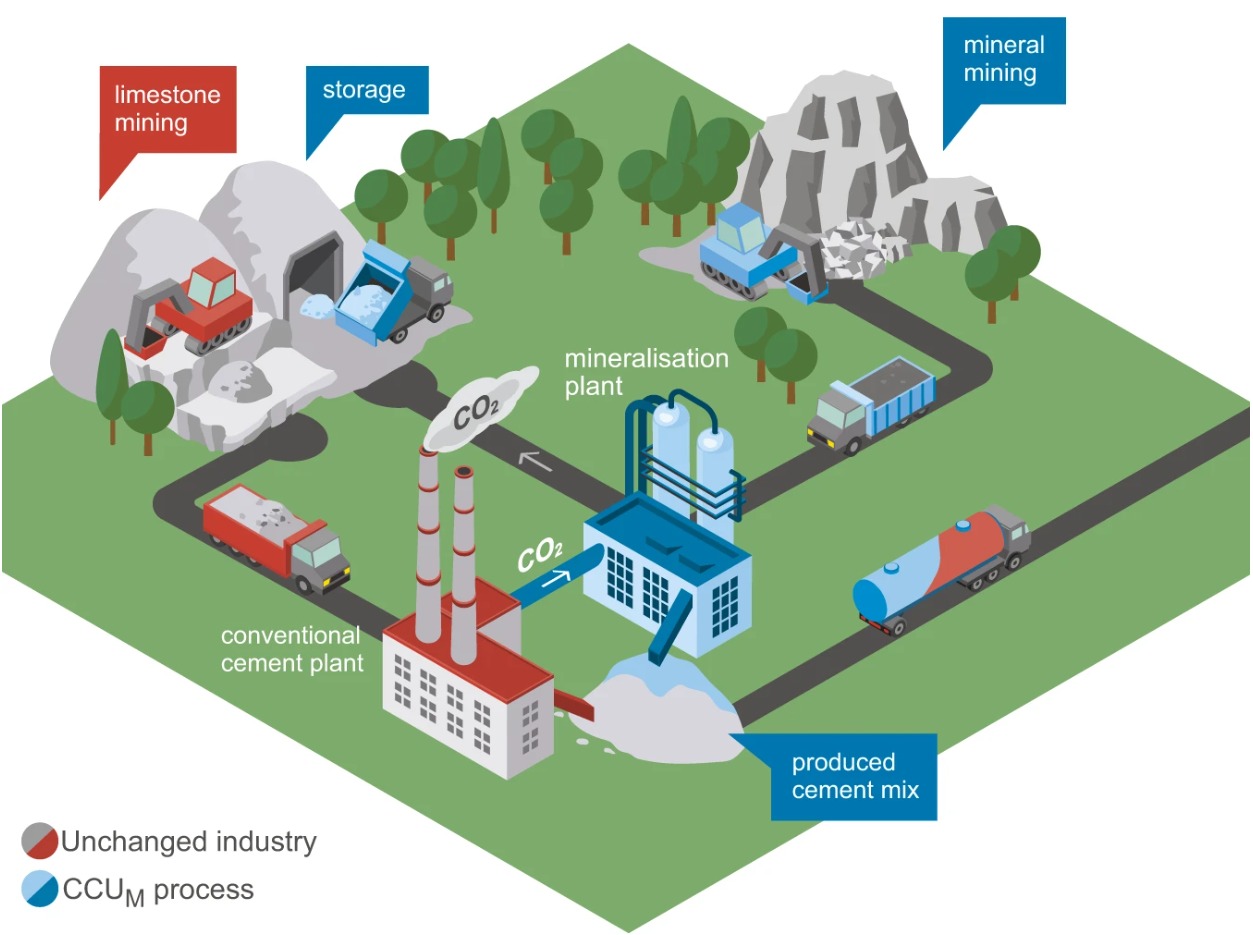

The German-Scottish collaboration has been looking at the process of CO2 mineralisation to create a form of carbon capture. In mineralisation, the captured CO2 is reacted with other minerals, such as magnesium or calcium-rich silicates, which can be stored indefinitely or used in the production of other products.

This latter advantage is of particular interest. Attempts to decarbonise the construction industry with other technologies or materials, such as carbon capture and wood, have been limited by their impracticability or economic infeasibility. The result of CO2 carbonisation, however, can either be sold as a separate product, or reverted into the production of concrete itself. For example, certain mineralisation compounds could be used as additives to cement, creating new less resource intensive blends of cement.

According to the authors of a study published in Communications Earth & Environment (Nature Portfolio) the resulting cement could reduce carbon emissions by eight to 33 percent, and bring in an additional profit of 32 EUR per tonne of cement. Currently, a metric tonne of cement sells for around 120 EUR – a record high.

However, the study also accepts several things need to change to make their mineralisation process profitable for companies. Regulations and bureaucracy around cement standards may need to be adjusted to allow for wider use of other blends, while the storage of CO2 in minerals must also be made eligible for EU Emissions Trading System credits or similar. Even if this becomes a reality, the study also stresses the need for subsidy programmes like those used in renewable energy to incentivise adoption.

But there are also other alternatives and methods being developed to clean up cement. One project is looking at injecting carbon back into cement to strengthen and reinforce it, while a recent project has turned to bacteria as a means of binding aggregate together into concrete. Another potential solution is looking to other building materials, such as recycled plastic, for growing urbanisation, or revitalising existing structures, such as decommissioned industrial buildings, into new generations of smart neighbourhood.