Carbon capture technology is increasingly being seen as one of the primary technologies to help heavy industry decarbonise its activities. On paper, the idea sounds like a great one. Carbon is captured before it ever enters the atmosphere and transformed into a more controllable state – usually a solid form.

However, as with many of these seemingly revolutionary technologies, there are often issues not far around the corner. Carbon capture can currently only be conducted at a relatively small scale, and often inefficiently. Some carbon capture technologies also require large amounts of energy and may result in other environmental issues, such as pumping liquid gas under the ground.

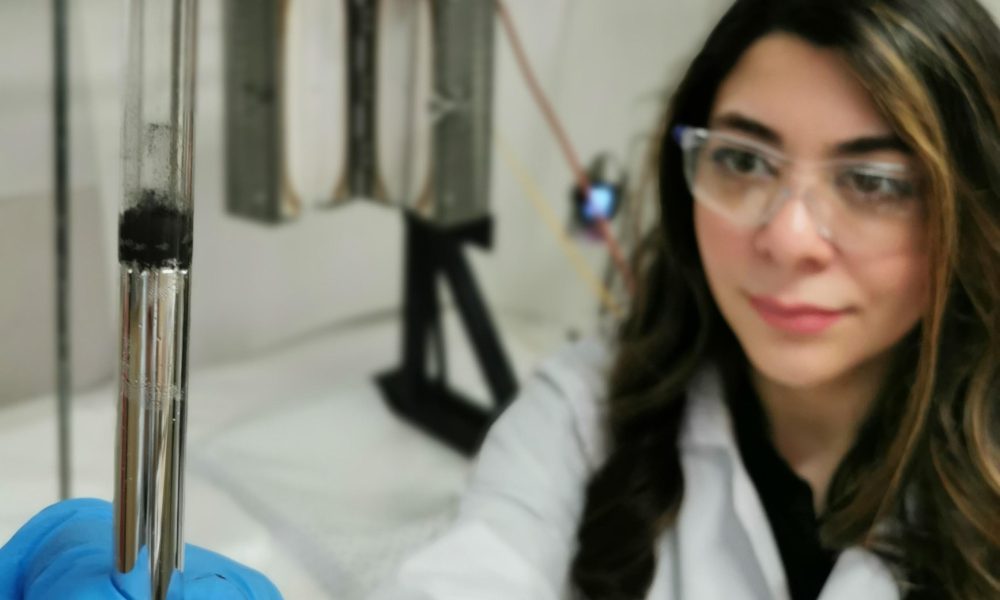

A new Australian breakthrough is hoping to solve some of these issues and make carbon capture more viable, and environmentally friendly. Researchers at RMIT University, Melbourne have developed a method to convert carbon dioxide gas into a solid form within seconds, and in a manner that can theoretically be easily scaled and added into existing production cycles.

The approach, laid out in the Energy & Environmental Science journal, employs thermal chemistry methods to create a “bubble column” of liquid metal. The metal, which is heated to around 100-120 degrees celsius, then has carbon dioxide pumped into it. The carbon dioxide rises as bubbles within the column, with the gas molecule breaking up into flakes of solid carbon. The huge advantage of this system is the whole process only takes seconds, which could make the approach more attractive, as co-lead researcher Dr Ken Chiang explains:

“It’s the extraordinary speed of the chemical reaction we have achieved that makes our technology commercially viable, where so many alternative approaches have struggled.”

A Key to Circular Industrial Economies?

Furthermore, the resulting carbon blocks could also be used in other applications, with the research team experimenting with turning them into building blocks. This will add a circular economy element to the approach and allow the carbon capture technology to pay for itself over time. Other carbon capture projects have looked at using repurposed carbon as both a fuel or fertiliser.

Another added advantage is the process uses fairly low temperatures, reducing the power demands of the system. As a result, the whole method could theoretically be powered by renewable energy.

The next step for the project is to develop the concept into a scaled up model which can be easily and seamlessly integrated into current production processes for dirty industries, such as concrete and steel. These sectors would particularly benefit from decarbonisation due to their high energy demands and the amount of carbon their production processes produce. They are also sectors which are only likely to expand in the coming future as population growth and the spread of urbanisation increases the demand for their products, especially in the Global South.

Ultimately, efficient, low-power carbon capture technology could potentially clean up these dirty industries and even provide an alternative revenue stream to companies. All of this may be necessary to encourage business-minded owners to add decarbonisation processes to their operations.

The RMIT ‘bubble column’ process has already grabbed some attention from the industry. It has partnered with concrete producer ABR to help construct its first prototypes, including a shipping container sized proof-of-concept model. This is not the universities first foray into carbon capture. In 2019, the university announced research which had essentially turned carbon back into coal, and at room temperature. Such developments are highly enticing to state governments, who have highlighted the potential of carbon capture systems. They are particularly attractive as they allow for heavy industry to continue in a decarbonised form, theoretically protecting jobs and maintaining economic development. However, many systems are still within their infancy and it remains to be seen if carbon capture can really become the holy grail of decarbonisation.