You don’t have to have spent a holiday on beaches full of plastic waste to know that we have a huge problem. Plastic islands in our oceans, seabirds with stomachs stuffed with colourful plastic pieces and turtles tangled in nets – most of us will have seen frightening images like these. But somehow it all seems so far away from us – at least until our next holiday. What fewer people know, however, is that alarming amounts of plastic aren’t only floating in our seas – it’s also found in almost all bodies of freshwater in Europe and around the world, although in the microscopic form of our favourite packaging material: microplastics.

The real extent of microplastic pollution is only slowly becoming clear; in addition to studies that demonstrate microplastic contamination in almost all waters in Europe and even in our drinking water, a study of German beer found microplastic in all 24 brands, and another found it in well as in honey and sugar. And in Paris, researchers have discovered microplastic particles literally falling from the sky and in the air in people’s homes.

What exactly is microplastic and where does it come from?

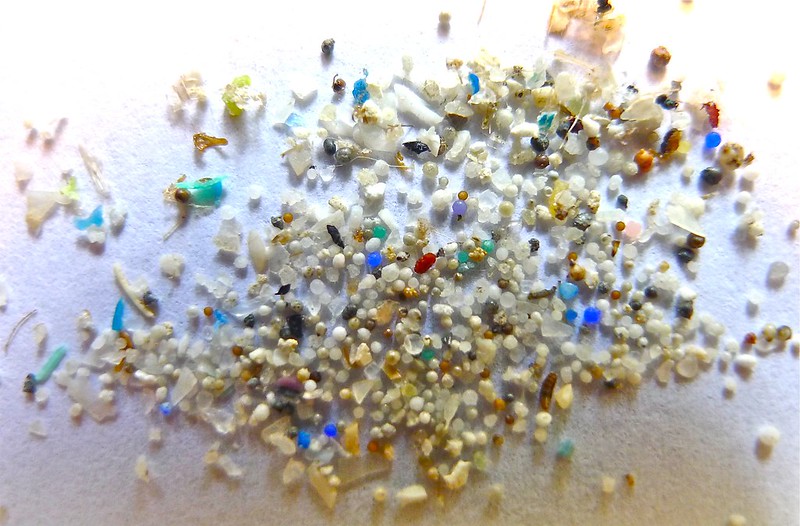

It’s a day just like any other: you get out of bed, brush your teeth, exfoliate quickly with your favourite face scrub and then wash your hair. Oh yeah, and there’s that laundry that still needs to go into the machine, and your new brightly coloured synthetic sweater along with it. Did you know that we’re also flushing plastic down the drain and into sewage system when we carry out these mundane, everyday activities? Probably not, because there’s nothing to see. Here we’re talking about small, even microscopic plastic pieces, from five millimetres in diameter down to nanometres that are invisible to the naked eye, also called microplastics or “microbeads”.

Microplastics in cosmetics and fabric

These microscopic plastic particles can be found in a huge range of everyday cosmetic products such as toothpastes, shampoos and peelings; added to create an abrasive, exfoliating or cleansing effect. While these microbeads make up only a tiny part of the tons of plastics which wash into the sea every year, they’re concerning enough for the US to have brought in a ban against them in 2015 and for the UK to have followed suit with a ban that came into force in January 2018. The story in different in other countries, however, with a study conducted by the consumer platform “Codecheck” in Germany in October 2016 showing that of 130,000 skin care products, one in three facial peels and one in four shower gels contained polythylene.

Microplastics also come from the fibres in our clothing – every time we do a load of laundry, tiny synthetic microfibres are released from our clothes and begin their long journey into the sea. The release of synthetic fibres such as acrylic, polyamide, elastane, polyester, etc. during the washing of textiles has proven to be one of the main sources of microplastics, both in domestic and industrial wastewater. It’s estimated that a single synthetic garment can release up to 1900 individual fibres each time it’s washed, and a recent report, from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that 35 per cent of all primary microplastics in the oceans originate from machine-washed synthetic textiles, making it the single largest source of microplastics. Car tyre wear was in second place. When these kind of plastic particles enter the water system, sewage treatment plants are unable to filter them out again – the tiny particles are simply too small enough for most filters to be able to catch.

One plastic bag = millions of plastic particles

Another source of microplastics is the when of larger plastic parts, e.g. due to weathering, wave movement and solar radiation. Plastic waste that’s produced on land and not properly disposed of ends up in the sea, carried either by our rivers and the wind. According to a study by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), plastic, especially in the form of bags, canisters and PET bottles, accounts for up to 80 per cent of all waste in the oceans. Exposed to the sun and waves, these plastic items break down into ever smaller particles, eventually becoming microplastics.

Microplastics in gardens and fields

Compost and fertiliser made organic waste is seen as an environmentally-friendly alternative to synthetic fertilisers. However, a new study has shown that organic fertilisers can also contain large amounts of microplastics. Researchers at the University of Bayreuth discovered up to 900 pieces of plastic per kilogram in fertiliser from biowaste fermentation. It was often still possible to see where the particles come from: sometimes plastic bags, packaging and other containers that mistakenly end up in the organic waste bin in people’s homes.

Leftover food from supermarkets is also often shredded up for use as substrate in sewage treatment plants and biogas plants. But unfortunately, not all plants take the trouble to remove the food leftovers from their packaging, meaning that the packaging material lands on fields and finds its way into waterways.

Microplastics in drinking water

It’s not only in rivers, lakes and oceans that microplastic has become a problem: microplastic contamination has been found in tap water around the world, with a huge 83 per cent of samples found to contain plastic fibres. A later study into bottled water found it to be even worse: over 90 per cent of all bottled water was found to show signs of microplastic contamination.

The US-based researchers were able to detect plastic residues such as polypropylene, nylon and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in 93 percent of the 250 samples tested from the USA, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Thailand and Lebanon. They found up to 10,000 particles in a single bottle, an average of 10.4 micro-plastic particles (0.10 millimeters) per litre. According to microplastics expert Sherri Mason of the State University of New York, the majority of the particles were fragments, and not fibres, leading the scientists to assume that the plastic is getting into the water during the filling process – either from the bottles themselves or from their lids.

So, what’s wrong with microplastics?

Because the particles are so small, they spread through rivers, lakes and seas and can be found there from the uppermost to the deepest layers of water. There they are ingested by animals who mistake them for food – until they end up on our plates in the fish we eat. Microplastics have already been detected in microorganisms (zooplankton), mussels, worms, fish and seabirds. And fish and mussels are food for marine mammals, birds – and us too. Studies revealed plastic in a third of all fish caught in England.

We haven’t yet finished investigating just how serious the damage is that microplastics in our ecosystems and living organisms causes, but various studies from recent years have shown worrying results.

Environmental researcher Anderson Abel de Souza Machado from the Leibniz Institute for Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) in Berlin warns: “Tiny plastic particles exist practically everywhere in the world and can have all kinds of different negative impacts.” Together with Matthias Rillig from the Free University of Berlin and other scientists, he was able to prove, for example, that earthworms carry microplastics from the surface of soils under the ground, where, sealed off from light and oxygen, it can last for over 100 years. Another study showed that earthworms that come into contact with the plastic particles dig their tunnels differently, which has a direct effect on soil conditions.

If ingested by humans and animals, the tiny plastic particles can have various different effects: some studies indicate that microplastics can penetrate body cells or organs and cause inflammation, changes in the permeability of membranes and stress due to free radicals. Quite aside from the fact that we (just like all other living beings) definitely don’t want to feed on plastic, plastic particles in the environment literally act as a “magnet” for harmful substances and their physical and chemical properties mean they bind toxic substances under water. The concentration of pollutants found in micoplastic particles is often a hundred times higher than in the surrounding seawater. In addition, the plastics themselves contains chemicals that are added during production. For example, phthalates and BPA (a common starting material for the synthesis of plastics) can have a similar effect to estrogen, the female sex hormones. Experiments have shown that they can disrupt the hormonal balance in many animals.

Even if it turns out that microplastics themselves are perhaps not the most dangerous environmental toxin that living beings have to contend with, the sheer scale of the contamination is means that it’s an enormous man-made stress factor that ecosystems worldwide are constantly being exposed to. So we should do all that we can to find out what the real risks are and to contain the possible dangers as soon as possible.

What can we do about it?

To get our global plastic problem under control, our most important goal should of course be to avoid plastic in any form and to work as hard as we can on developing and promoting alternatives. Clear political regulations form a part of that.

Although some of the substances are considered to be hormonally active or carcinogenic, in Europe there are few legally binding bans for manufacturers on the use of microplastics in their products – with the exception of Sweden and the UK. In recent years, many of the largest international cosmetics producers have agreed, under public pressure, to make a voluntary commitment to removing the controversial plastic particles from their products. But according to a report by Greenpeace, among the top highest-selling manufacturers worldwide, there’s very little commitment to change. It’s not as if there’s no alternative to putting microplastics in cosmetics: manufacturers of natural cosmetics have long relied on sugar-, silica- or medicinal clay-based alternatives.

And when it comes to packaging there are alternatives too, the use of which should be encouraged. Huge amounts of conventional plastic packaging could be replaced by edible packaging made of milk proteins or seaweed, plant-based bottles made from sugar cane and biodegradable packaging made of wood-shavings.

We also have to take steps to try and catch plastic waste before it makes its way towards our seas. Innovations like the Guppy Friend laundry bag and Cora Ball can make your laundry microfibre free, while digital tools can be used to find illegal dumping sites and organise community cleanups and new processes make plastic recycling more efficient.

And last but not least, we should do what we can to remove any plastic from our ecosystem that is already there. Visionary researchers are developing ships that can fish plastic out of the ocean: like the Ocean Cleanup Project and the giant litter-picking quadrimaran “Manta”. A process developed by Swedish researchers using a semiconductor and the power of the sun offers one possibility of breaking down microplastics into harmless substances, and bacterias and enzymes have also been discovered that destroy plastic by literally eating it up.

And you can help too!

What can you do to stop plastic microfibres shedding off your clothes and going down the drain? The Plastic Pollution Coalition has come up with 15 simple ways you can help.

Live in a country where microbeads haven’t been banned yet? Beat The Microbead has a comprehensive list of microplastic-free personal care products for countries throughout the world.

Want to put an end to plastic madness in your own home. We’ve put together a few tips: 7 Quick and Easy Ways to Reduce Your Plastic Consumption