78 million batteries will end up in the rubbish every day by 2025, according to a recent EU study. And, as they corrode, their chemicals will slowly leach into the soil and water. These will go on to contaminate entire ecosystems, their effects lasting for generations. Batteries certainly aren’t going anywhere fast. Global demand for these vital power sources is also increasing rapidly, and is set to increase by 14 times by 2030. The EU alone will contribute to this figure by around 17 percent, in spite of the 2023 Batteries Regulation that ensures that batteries are sustainable and circular throughout their life cycle. It goes without saying—finding greener alternatives to batteries would help us reduce a large amount of this toxic waste.

A new type of mechanical sensor, developed by researchers led by Marc Serra-Garcia and ETH geophysics professor Johan Robertsson, could offer one such alternative.

Powered by sound waves

Sensors, particularly those used for medical or infrastructural purposes, typically run on batteries around the clock. These batteries eventually run out and are discarded. However, the sound-powered sensor developed by Serra-Garcia and Robertsson “works purely mechanically and doesn’t require an external energy source. It simply utilises the vibrational energy contained in sound waves,” says Robertsson.

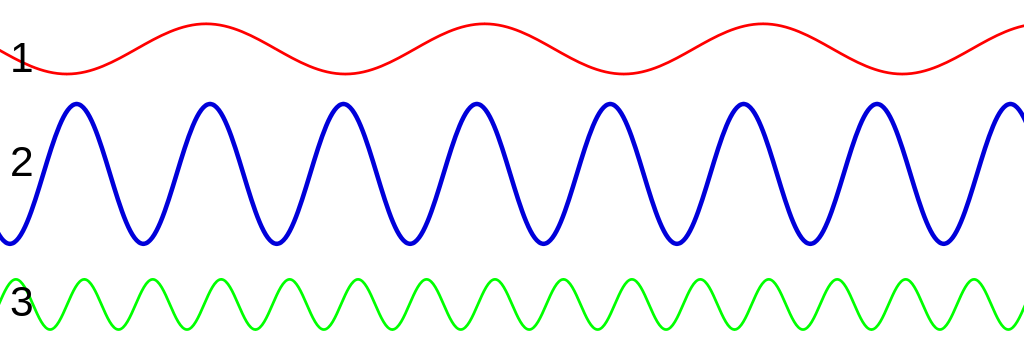

All sounds are created by distinctive sound waves. These are unique, much like a fingerprint, and this sensor works by recognising and then reacting to their specific characteristics. Whenever a certain word is spoken or a particular noise is generated, the sound wave emitted vibrates the sensor. The energy caused by this process is powerful enough to generate a tiny electrical pulse that switches an electronic device on.

For example, it can distinguish between the soundwaves emitted by the words “three” and “four”. The word “four” could switch on a device or trigger further processes, whereas nothing would happen with “three”.

Newer variants of the sensor should be able to distinguish between up to 12 different words, such as standard machine commands like “on”, “off”, “up” and “down”.

A unique structure is essential to the sound-powered sensor functionality

The secret to the sensor’s functionality lies in the genius of its design. It comprises of dozens of identical or structured plates, connected by tiny bars which act like springs. While a strictly analogue design, researchers used computer modelling to work out how to attach the bars and plates together to best determine whether or not a particular sound source sets the sensor in motion.

While the prototype was roughly palm-sized in its inception, the new versions are about the size of a thumbnail, making it far more practical. And, the researchers are aiming to miniaturise them further.

“Our sensor consists purely of silicone and contains neither toxic heavy metals nor any rare earths, as conventional electronic sensors do,” Serra-Garcia says.

This simple sensor could have a big real-world impact

Sensors are everywhere and have myriad uses. Battery-free sensors could, for example, register when a building develops a crack that has a specific soundwave. The fact that the battery would not have to be constantly running to spot a sound that might come once in a generation would save vast amounts of energy and numerous batteries.

Another important use case is the monitoring of decommissioned oil wells. Gas can escape from leaks in boreholes, producing a distinctive hissing sound. A mechanical sound-powered sensor could detect the specific hissing sound and then trigger an alarm without the need for continuous electricity consumption. Not only is it cheaper to run and a low-energy solution, but it would also reduce maintenance requirements.

The researchers also foresee the technology being applied to medical devices, including cochlear implants. These hearing prostheses for the deaf need a constant power and usually require a new battery every 12 hours.

Its creators have already applied for a patent and have presented the principle in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

Their aim is to launch a solid prototype by 2027. The researchers already anticipate a struggle to drum up sufficient funding. However, a plan is in place to push the project forward: “If we haven’t managed to attract anyone’s interest by then, we might found our own start-up.”