Digital tools and services are an integral part of our lives. It’s hard to imagine a life without smartphones, apps, Wikipedia, online banking, route planners with GPS and having a huge selection of music and movies at your fingertips pretty much everywhere, around the clock. All of these things make our lives so much easier. But it’s not only in day-to-day life that digitalisation has become indispensable; digital technologies are also playing an increasingly important role in agriculture and industry, in the transition to renewable energies and in the future of our cities. At the same time, digitalisation offers new solutions for tackling climate change and protecting the environment. Reporting on them is an important part of what we do here at RESET.

However, just because we can’t physically see or touch the data that we’re sending and receiving all over the globe, it actually carries rather heavy baggage: its energy consumption is constantly growing, the smart devices we use are often produced under exploitative and environmentally harmful conditions and, at the end of their far too short lives, they end up as toxic electronic waste. This poses a very important question: will digitalisation be able to help us on the way to a greener and fairer world, or will our growing reliance on digital tools ultimately prove to be an accelerator for climate change and the destruction of the planet?

Right now, the question is still open. Let’s take a closer look at the main causes of our digital carbon footprint – and also who and what is working to mitigate its climate impact.

How big is the world’s digital carbon footprint?

More than half of the world’s population is now online. According to Statista, more than 5.35 billion people used the Internet in 2024. And with online activities such as cloud computing, streaming services and cashless payment systems on the up, the demand for online and digital services is constantly growing.

The non-profit organisation The Shift Project (PDF) looked at nearly 170 international studies on the environmental impact of digital technologies. According to the experts, their share of global CO2 emissions increased from 2.5 to 3.7 percent between 2013 and 2018. That means that our use of digital technologies now actually causes more CO2 emissions and has a bigger impact on global warming than the entire aviation industry! According to estimates, the aviation industry caused around 2.5 percent (and rising) of emissions.

These figures may vary slightly from study to study, as the energy consumption of digital technologies is difficult to quantify: because too little data is available, because technological advances and changing consumption habits cause them to change rapidly and because they’re highly dependent on certain conditions (for example, the type of power that’s being used). Researchers in a new study criticise the fact that the Shift Project figures were calculated using outdated data.

The short study “Climate protection through digital technologies” (Klimaschutz durch digitale Technologien) from the Borderstep Institute compares various studies and comes to the conclusion that the greenhouse gas emissions caused by the production, operation and disposal of digital end devices and infrastructures are between 1.8 and 3.2 percent of global emissions (as of 2020).

Even if it’s hard to work out specific figures, it is clear that our digital world has a huge energy appetite, especially if you include not only the use, but also the production, of our digital devices.

What digital activities are using the most energy?

Jens Gröger, senior researcher at the Öko-Institut, estimates that each search query emits around 1.45 grams of CO2. If we use a search engine to make around 50 search queries per day, this produces a huge 26 kilograms of CO2 per year.

Doesn’t sound like a lot? Not at an individual level. But Google itself, in its 2017 Environmental Report 2017, puts its carbon footprint for 2016 at 2.9 million tons of CO2e and its electrical energy consumption at 6.2 terawatt hours (TWh).

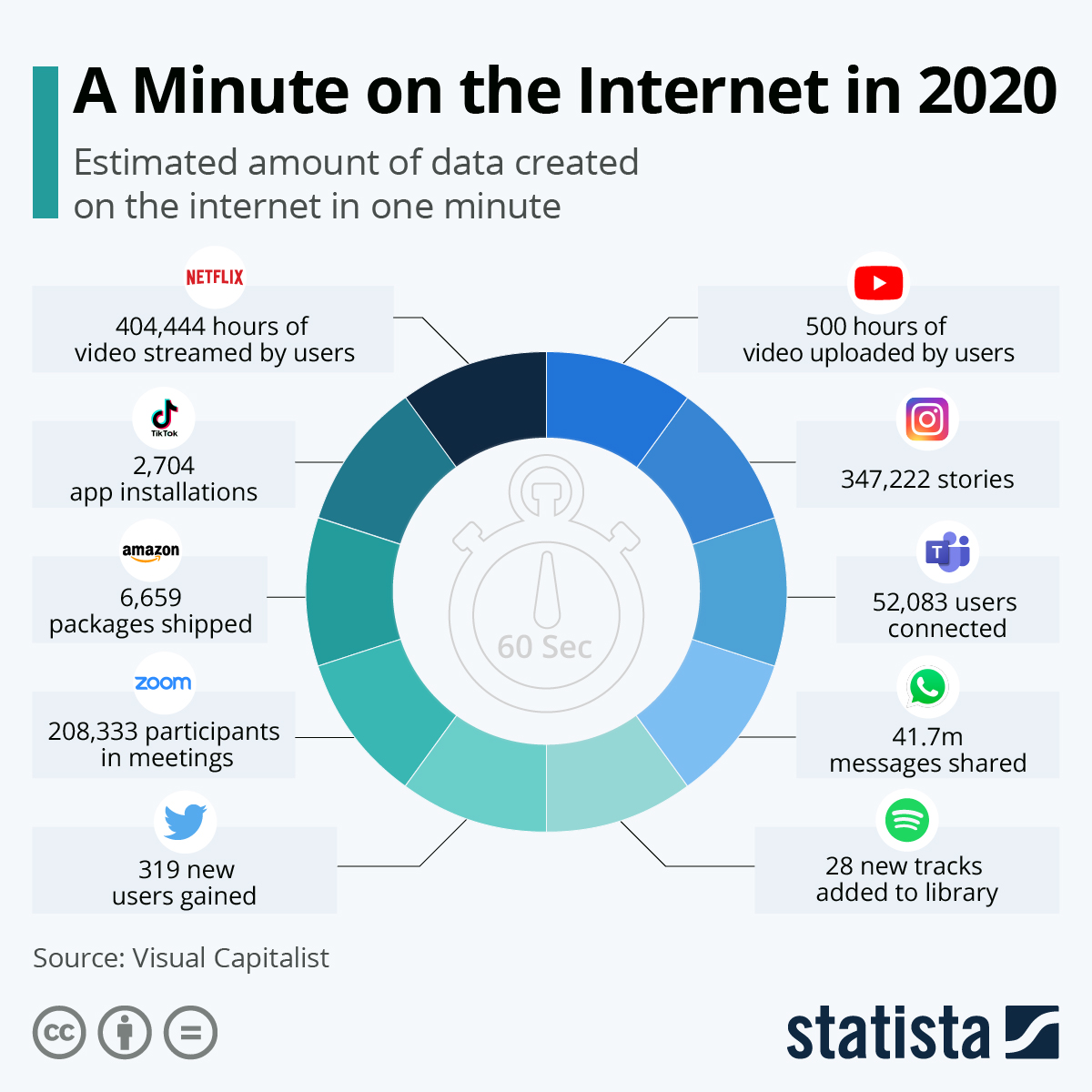

But online searches are by no means the core of the problem: one of the biggest causes of the internet’s huge power consumption is in fact music and video streaming. According to research by The Shift Project, 80 percent of all data flows through the net in the form of moving images. Online videos – available on different platforms and viewed without being downloaded – account for almost 60 percent of global data transfer. Transmitting these moving images requires huge amounts of data. And the higher the resolution, the more data is sent and received.

According to The Shift Project, the average CO2 consumption of streamed online video is more than 300 million tons per year (based on measurements taken in 2018). This is the same as emitted by the whole of Spain in a year. Another comparison out of interest: streaming ten hours of film in HD requires more bits and bytes than all of the articles in the English Internet encyclopedia Wikipedia put together.

Another analysis suggests that streaming a Netflix video in 2019 typically consumed 0.12-0.24 kWh of electricity per hour, about 25 to 53 times less than the Shift project estimates. Ralph Hintemann at the Borderstep Institute for Innovation and Sustainability stresses that while video streaming causes high greenhouse gas emissions, no one knows exactly how high the figures are. Concrete figures are difficult to determine because the results depend heavily on the choice of device, the type of network connection and the resolution.

Using the internet on a mobile phone uses the most power, because buildings, vegetation and weather weaken the electromagnetic waves. That means that higher transmission power is required. But even with old copper cables, the signal has to be amplified, especially over long distances. Fibre optic cables, which transmit the signals via light, are definitely the most efficient form of transmission technology. Powered by the average global electricity mix, streaming a 30-minute show on Netflix would currently release 28-57 grams of CO2. This is about 27 to 57 times less than the 1.6 kg from the Shift project. Ralph Hintemann and his research group have calculated that streaming one hour of video in full HD requires about 220 to 370 watt hours of electrical energy, depending on whether the video is streamed via tablet or TV. This adds up to around 100 to 175 grams of carbon dioxide and would be about the same as driving one kilometre in a small car.

Music streaming also comes off quite badly: a new study by the universities of Glasgow and Oslo shows that music streaming services emitted around 200 to 350 million kilograms of greenhouse gas in 2015 and 2016. That means that using streaming services such as Spotify or Apple Music is in many cases more harmful to the climate than the production (and subsequent disposal) of CDs or records.

Cloud computing is another major power guzzler. This is where data is no longer stored locally on a computer or smartphone, but on servers that can be located anywhere in the world, meaning it can be accessed anytime and anywhere. Checking your email via gmail and backing up your photos to the cloud are just two examples of these kind of services.

Most cryptocurrencies also consume large amounts of energy. One example of this is Bitcoin, probably the best-known digital currency. According to calculations by the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index (2018), a single Bitcoin transaction consumes around 819 kWh. The same amount of energy could operate a 150-watt refrigerator for about eight months. And in a 2018 study, the Technical University of Munich determined that the entire Bitcoin system produces around 22 megatons of carbon dioxide per year, the same as the CO2 footprint of cities such as Hamburg, Vienna or Las Vegas.

But it’s not only the Bitcoin blockchain that’s energy-intensive. Other blockchains and distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) also entail a huge demand for energy. In our recent RESET Special Feature looking at how blockchain can be used for real-world positive impact, we delved even deeper into the question of whether blockchain and sustainability can ever truly go together.

Our digital energy consumption isn’t only determined by what we do, but also how we do it; the software we use also has a big impact. For example, a less efficient word processor needs four times as much energy to process the same document as an efficient one. While at the same time, software updates often cause computers or smartphones to slow down or stop working, forcing consumers to buy new hardware.

And in the future, digitalisation’s growing demand for electricity will certainly also be driven by an increase in smart technologies, such as those we are increasingly using at home, in the IoT sector, in industry and in our increasingly digitalised cities.

All roads lead to… energy-hungry data centres

Every action, no matter how small, that is carried out online, travels in the form of a data packet through data centres and their servers. Looking at the energy use of data centres therefore gives us an idea of just how energy-hungry digitalisation is. It’s impossible to say with any certainty how high the current energy requirements of all data centres worldwide are. Current estimated calculations range from 200 to 500 billion kilowatt hours per year, an estimated percent of the world’s electricity. And future predictions differ considerably too – with figures between 200 billion and 3,000 billion kilowatt hours predicted for the year 2030.

Why do expert opinions differ so much? One reason is that there are no official figures for data centres yet. Another reason is that many operators are reluctant to provide information about their energy consumption due to concerns about security and competition. Researchers can therefore only get close to the real figures via detours, such as sales figures for servers or estimates from surveys.

And what exactly is using all that power?

First and foremost, a lot of power is needed to process the enormous data streams that we constantly send and receive via our devices. And when that data is processed, heat is generated as a waste product. To prevent the servers from overheating, additional energy is required for ventilation and to cool the servers down. On average, mechanical cooling is responsible for around 25 percent of the total power consumption of a data centre. And all that heat that’s producted? Usually it’s just released into the atmosphere – simply left to go to waste.

How can swimming pools make data centres more energy efficient?

Reducing the energy consumption of data centres is an important step towards making digitalisation more sustainable. There are three main ways to do that:

1. Finding the most efficient ways to cool data centres

One fairly simple-sounding and popular solution is to locate data centres in cooler countries and simply blow the outside air into them. This explains the multiple data centres located near the Arctic. Warmed, piped water is another way to cool banks of high-performance, hot computers, as is immersion cooling. Some companies are even working on using artificial intelligence to tune their cooling systems to match the weather and other fluctuating factors – in a bid to reduce their energy bills.

2. Re-using the waste heat

Data centres produce heat throughout the year. Ideally, this heat should be constantly be extracted and reused elsewhere. But finding the right customers to recycle that heat can be a challenge. Many newer data centres use the waste heat within the data centre itself. But, in order to better exploit the potential of waste heat, a more comprehensive approach is needed. While Sweden is one of those countries that is considered an ideal location for data centres because of its cool climate, at the same time, it’s also a pioneer when it comes to reusing their waste heat. The country relies heavily on a system of district heating (where heat is distributed via pipes to residential and commercial buildings from a centralised location), which makes it relatively easy to feed the waste heat from data centres into the network, thus heating the apartments that are connected.

The Elementica facility is the latest example. Fully expanded, the data centre is expected to recover up to 112 gigawatt hours of heat per year, covering the heating of tens of thousands of households. Another example is the Stockholm Data Parks initiative, which sees waste heat recycling as playing a key role in the city’s goal to be completely fossil fuel-free by 2040.

It’s also possible to feed the excess heat not only into local and district heating networks, but also into buildings such as swimming pools, laundries or greenhouses – places which permanently require heat. The first examples of this already exist. In Paris, a swimming pool is being supplied with heat from the servers of the animation studio next door. And, the Irish company Ecologic Datacentres is currently planning a computer centre that will use the waste heat to help grow vegetables in greenhouses and heat nearby homes.

The EU-funded ReUseHeat project is also working on innovative solutions for waste heat recovery. Nine European countries are to join forces over the next four years to make waste heat available at various locations in Europe.

3. Powering them with green electricity.

If data centres are ever to be operated in an environmentally friendly, maybe even one day carbon-neutral way, they will have to be powered by clean, renewable sources of energy. While most countries’ energy mix still only contains a small fraction of renewables, some companies are starting to focus more on sourcing their very own energy – from wind or solar power.

Founded in April 2015 in German North Frisia, the startup Windcloud start-up uses energy from local wind farms to power its data centres. Its provided 2015, Windcloud has provided IT services from 100 percent locally generated and renewable energy. Hostsharing e.G. has a different approach. The webhoster is organised as a cooperative and focuses on resource-saving webhosting using cooperative energy and the use and support of open source software.

We also use a green service provider to host RESET.org. Hetzner Online uses electricity from renewable sources to power the servers in their own data centre parks.

Have your own website? You can check its carbon impact using the online Website Carbon Calculator as well as find tips on how to improve it.

If we’re ever going to seriously shrink the carbon footprint of data centres, then we need to bring in policy regulations that restrict their energy consumption and incentivise efficiency measures. Right now there is little motivation for data centre operators to do the right thing.

The ecological and social impact of our smart devices

While Silicon Valley is already working on microchip implants that, once planted under the skin, will give us automatic access to the digital world, right now we still rely on smartphones, tablets, computers and other smart gadgets – and a lot of them. Our obsession with electrical gadgets is responsible for the fastest-growing portion of the world’s garbage problem. According to statistics from the UN, an estimated 50 million tons of electronic waste are generated worldwide each year – and the trend is rising.

The consequences for people and the environment are fatal. More than half of the electronic trash we produce is shipped cheaply to countries of the global South. There the valuable raw materials are extracted, often under inhumane and unhealthy working conditions, causing pollution in the local environment. At the same time, most of the mineral raw materials used in our smart devices come from countries where there is a disregard not only for labour rights but also for environmental standards. The same applies to the entire manufacturing process.

However, there are a growing number of companies and initiatives that are using sustainable materials, smart recycling methods and conscious use of raw materials to step away from a purely linear economy, using circular manufacturing methods that conserve resources and ensure fair working conditions.

It’s still quite a niche market, and there are no official certifications or political efforts for ethically-made electronics. However, there are a few eco-pioneers: Fairphone and Shiftphone have set out to show that consumer- and environmentally-friendly design is possible by making smartphones modular and easy to repair. At the same time, the companies pay attention to fair wages and working conditions, do without child labour and focus on resource-conserving production.

The Berlin startup MineSpider is approaching the topic from a slightly different angle: With the help of blockchain technology, MineSpider wants to ensure that no conflict minerals end up in our gadgets – by reliably tracking the supply chain for responsibly-mined minerals and raw materials that end up in manufacturers’ mobile phones and laptops.

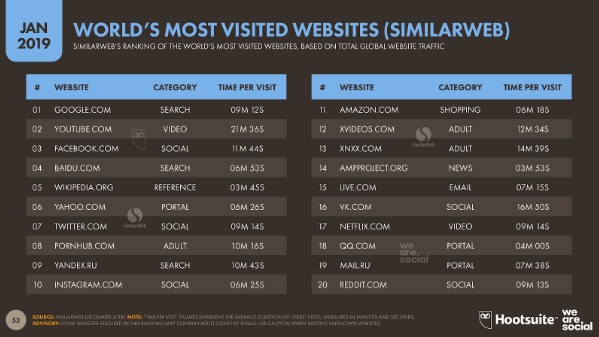

Monopolisation and platform capitalism

While in 2007 50 percent of the traffic on the internet was generated by over a thousand websites, by 2014 it was just 35 websites (“Warum brauchen wir Vielfalt?”/Bits & Bäume, p. 86). And of the 500 most visited websites worldwide, Wikipedia is actually the only one that is not operated commercially. So it’s not surprising that six of the world’s ten largest companies are now firmly rooted in the digital economy: Apple, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook and the Chinese company Tencent. Just a few global corporations hold an incredible amount of social and economic power.

From a socio-ecological perspective, this monopolisation and the increasing dependence on a small number of large platforms that results is cause for concern. In addition, recent studies suggest that digital platforms – with their on-demand culture and personalised online advertising – are accelerating more consumption and even increasing resource consumption through packaging waste and parcel deliveries.

The rise in personalised advertising and offers online – where information is gained about individuals through online data tracking and collection – is another negative aspect of this development: our private lives are increasingly being invaded by the financial interests of commercial companies. Digitalisation can only ever be truly sustainable if it takes not only ecological aspects into account, but also contributes to improving social and economic justice.

But there is another way, as civil society counter-movements to this development show. While they may not have the size and scope of the mainstream commercially-run alternatives, there are a few initiatives where the focus is on social-ecological values rather than profits. An example of this is the Fairbnb platform, which wants to offer a fair alternative to Airbnb. The platform was founded by neighbours and users as a cooperative, not as a company, and profits are driven back into the local neighbourhoods.

Digitalisation – Blessing or curse for the environment and society?

It is tricky to come up with a black-and-white answer to whether currently, digitalisation has a mostly positive or negative impact on the world around us. Digital technologies can help enable sustainable development by, for example, allowing people to share resources online, enabling innovative, resource-efficient production processes (like 3D printing) and speeding up the switch to renewable energies by opening up access to smart, decentralised energy networks. Digital platforms and apps can also help promote more environmentally friendly consumption and lifestyle options, for example by sharing tips on sustainable behaviour or simplifying access to environmentally friendly shared transportation. Sensors and satellites can help to highlight and locate environmental destruction and allow for rapid, targeted action.

However, as this article shows, digitalisation is energy-hungry and resource-intensive. It comes with a mighty carbon footprint that we might not be able to see, but we shouldn’t be able to ignore. We will only ever be able to achieve truly sustainable digitalisation if we learn to use digital tools and services in moderation and in the right places. We need to look at the issue of sustainability throughout the entire life cycle too, continue working on optimising our energy use and energy sources, and look more often for alternatives to the big players of our digitalised world. Equally crucial for a sustainable digital future – more manufacturers making ethical technology that respects both society and the environment, and more consumers supporting them by making the right choices.

We need manufacturers, consumers and digital service providers to make the right decisions when it comes to the environmental impact of our increasingly digital lives – and the incentive for that will ultimately come from policies and regulations being made (and respected) at an international level. Without decisive political action, the digital revolution is set to increase our consumption of resources and energy and accelerate the damage we are doing to our planet and our climate. While at the same time, certain unchecked digital developments threaten to undermine crucial pillars of free and democratic societies. Ensuring that digitalisation is placed at the service of sustainable development, and that digitalisation itself is executed and applied in a sustainable way, is an urgent political and social priority.

Sources and links

- Datacenter Insider: Abwärmenutzung ist der Schlüssel zum grünen Rechenzentrum

- Datacenter Insider: Schweden beschließt drastische Senkung der Stromsteuer

- ZDF: Planet E – Stromfresser Internet

- University of Glasgow/ University of Oslo: Music consumption has unintended economic and environmental costs

- BUND: Der Stromverbrauch der Bitcoin

- SWR: Ökobilanz des Internets

- IKZ: Abwärmenutzung aus Rechenzentren

- The Shift Project: Lean ICT – Towards Digital Sobriety. Report 2019 (pdf)

- Boderstep Institut: EU-EcoCloud – Wie kann die Energieeffizienz des Cloud Computing weiter verbessert werden?

- Borderstep Institut: Energiebedarf von Rechenzentren steigt weiter stark an

- Ökoinstitut e.V.: (In)Effiziente Software

- Klimareporter: Digitale Klimakiller

- Steffen Lange/ Tilman Santarius: Smarte grüne Welt? Digitalisierung zwischen Überwachung, Konsum und Nachhaltigkeit. Oekom Verlag/ 2018

- Anja Höfner/ Vivian Frick (Hrsg.): Was Bits und Bäume verbindet – Digitalisierung nachhaltig gestalten. Oekom Verlag/ 2019

- sustainable-digitalization.net

Authors: Sheena Stolz and Sarah-Indra Jungblut / RESET Editorial (August 2019)

Updated in March 2024 (Lana O’Sullivan)