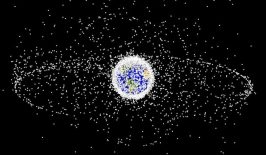

The 12 Copernicus satellites of the European Space Agency (ESA) deliver around 250 terabytes of data every day – sending us huge amounts of valuable information about the state of our planet each and every day. The high-resolution images can reveal, for example, human rights violations, illegal deforestation and overfishing. They can also help assess the impact of environmental and climate protection measures and coordinate disaster relief efforts. We took a closer look at all of these and more in our recent RESET Special Feature “Satellites for Sustainable Development”. Click here to explore all of the articles in the series.

However, in order to retrieve and analyse that data from the satellites, users require a large amount of both technical and professional knowledge. That could soon change however. With his project OpenSpaceData, software developer Niklas Jordan wants to give citizens, journalists and NGOs easy access to socially relevant information, regardless of their level of technical knowhow – with the help of a centralised database filled with all publically available satellite data and a simple search tool.

OSD is funded by the Protoype Fund, a project of the Open Knowledge Foundation Deutschland e. V., which in turn is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

We spoke with Niklas Jordan about his personal motivation behind the OpenSpaceData project, how he’s going about putting into practice, and the challenges he’s facing along the way.

Photo: Niklas Jordan

Niklas, what motivated you to start OpenSpaceData?

I have been working with satellite data for many years. In my opinion, it’s the untapped gold of the future. The data is openly available to everyone. In other words, anyone can access a huge treasure trove of environmental information. Unfortunately, many people don’t know about this “treasure” or how they can use it for themselves.

I’m a software developer and have been studying geoscience for a few years alongside my job – so I have the best prerequisites for using this satellite data. Because the entry hurdle to using the data is quite high: at best, you need to have a basic knowledge of programming and an understanding of how satellite programmes work. So with my skills, I am absolutely privileged compared to people who have never been involved with Earth observation or programming before. Many people don’t have the means to access the data or work with it. That annoyed me. I am convinced that everyone – whether a student, journalist or activist – can benefit from this data.

What challenges do you hope to be addressing?

Many people talk about open data. Open data is great. It ensures that we get machine-readable data sets of socially relevant topics that would otherwise gather dust in filing cabinets. What we often forget in the process: Open data must also be accessible to everyone. Currently, open data is mostly only for very tech-savvy people, because they are large databases that can only be read with certain programmes. We can only create accessibility through offers that are as low-threshold as possible, for example through graphical user interfaces that can be used by anyone, that do not require advanced technical skills and that speak a language that everyone understands.

So we needed a solution to the problem. I researched for a few months. I tested. In the end, I was always disappointed. There are great tools to facilitate access to Earth observation data, but unfortunately they are always aimed at professional users. Many of them are also aimed at beginners in the way they communicate, but in the end they always have to make a compromise: efficient tools for professional users vs. a simple as possible user interface for beginners.

That’s why I wanted to develop a tool that focuses explicitly and exclusively on first-time users, but also doesn’t compromise when it comes to professional users either.

How does OSD work exactly?

The app is currently still in development. But the plan is this: OSD does not require any programming skills or prior knowledge of Earth observation data. In other words, the interface doesn’t assault you with technical terms or require any complex inputs. Users only need to specify three things:

1. What do I want to analyse? Here, the users can choose from various predefined use cases. For example, whether the health of the vegetation should be determined or the effects of drought on a particular lake.

2. Which location or area am I interested in? Users can select a specific area by entering a search term, similar to well-known mapping services such as Google Maps, or select an area on the map.

3. Which time period should be analysed? The earth is constantly changing. Therefore, changes on the earth’s surface must always be seen in a temporal context. Users can therefore specify whether they want the most recent data or the data from a certain period, for example from a certain month of a certain year.

And that’s it. Our algorithm will ensure that users get the best possible satellite image and provide them with guidance on how to use the data, analyse it and then derive the right insights from it.

© So soll die Benutzeroberfläche aussehen.

© So soll die Benutzeroberfläche aussehen.That sounds simple. It’s not though, is it?

The simple-sounding goal of OSD picking out the “best possible satellite image” for the user with the three specifications is also the biggest challenge. The quality of satellite images can vary greatly and depends on many different factors: the area to be viewed, the time of day the image was taken, the weather conditions on that day, and much more. The algorithm has to make many decisions to give the users the result they expect. A cloudy image might be completely useless for the analysis and our tool would not be of much help.

Can anyone really access satellite data using OSD without prior knowledge? Could I, for example, view the water level of a lake over the last ten years?

Yes, that is our goal. However, it should be clear that we are not delivering the umpteenth tool that will relieve users of all processing and analysis steps. A big difference to other tools, as well prioritising first-time users as a target group, is that we want to empower people. We focus strongly on education. This means that we provide users with the right data and step-by-step instructions on how to analyse the water level of their lake. But they will have to do the analysis and editing of the data so that they can read their information correctly. This ensures that they become familiar with the subject and also understand what this has to do with the data in order to arrive at a certain result. Our goal is that they can then go further on their own and have enough basic knowledge in dealing with Earth observation data to continue working with more professional tools.

That demonstrates one crucial point of our strategy: we offer the easiest possible access for first-time users and do not rely on the users working with our solution permanently. If users are able to go on to using professional applications, then our project has been successful. Because then we have fulfilled our mission: To show what is possible with Earth observation data, how it can help everyone, and to educate them to the point where they can understand and use it. We are just providing an entry point into the field of Earth observation, not the full solution.

What do you think, will we all work with satellite imagery as a matter of course in the near future, not only scientists, but also the general public?

That’s what I hope. And I believe that in the medium term, that will be the case. The whole field is experiencing a huge influx of people working on the topic and companies are building new products on this data. New tools are emerging all the time, both commercial applications and tools provided by the space agencies like ESA themselves, which allow us to use complex data via simple applications. And once you’re bitten by the Earth observation bug, there’s no going back!

This is a translation of an original article that first appeared on RESET’s German-language site.