Prof. Dr. Martin Stefan Brandt is head of the international research team which discovered billions of trees where nobody would have expected: in the desert. Brandt, who studied geography in Erlangen and received his doctorate in Bayreuth, is working at the University Copenhagen since 2015.

Mr Brandt, together with an international team of scientists, you mapped the tree population in arid parts of Mauritania, Mali and Senegal and came up with some astonishing results. What exactly did you find?

We found that there are billions of trees growing in areas that we previously thought to be desert or grassland.

How did you get to that conclusion?

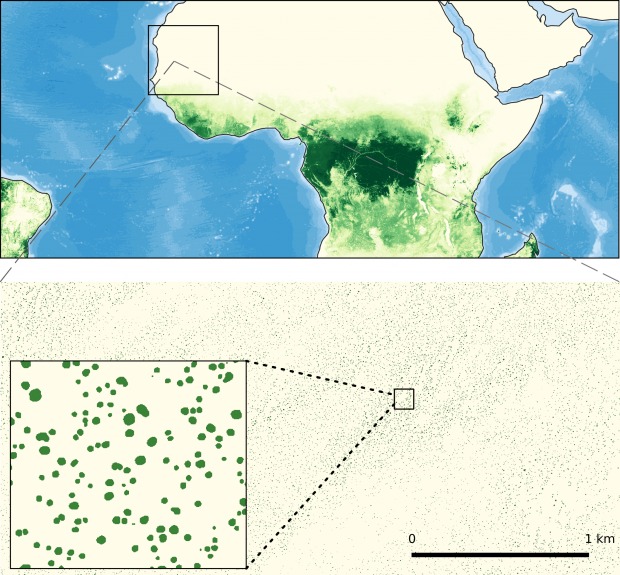

Our results show 0.7 trees per hectare in the western part of the Sahara and about 30 in the semi-arid zone of the Sahel. Our survey has made trees visible that were previously not on any map in the world. Trees in the Sahel grow mostly on their own, and it hadn’t been possible to detect them in satellite images until now because the resolution of previous sensors – at ten to thirty metres – wasn’t high enough. It’s surprised many people that trees growing individually, not as part of a forest, can actually have such a high density.

You are working with satellite data which has a much higher resolution is far better than that previously used for mapping. Which satellites and data are you using?

Such detailed mapping is currently only possible with commercial high-resolution sensors. We work with optical data from the Worldview satellites, operated by Maxar, which map surfaces to within 50 centimetres.

You examined an area three times the size of Germany. How did you go about evaluating it?

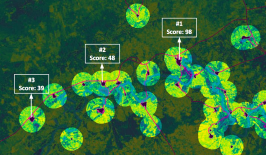

The process is simple: You show the computer examples of trees and it learns from them in order to be able to recognise the element “tree”. We then ran the algorithm over thousands of images. The computer evaluates what it has been taught. However, it can do in minutes what would take a human being years.

What do the results mean for the region, and also for global climate models?

For the people in the region, the results are fairly insignificant for now. After all, no new trees are growing as a result of our research. However, this kind of mapping could be very valuable for national and regional management. Our discovery will also have significance for climate models, but this needs to be investigated in more detail. Arid areas will definitely have to be much better integrated into climate models in the future, since right now they are simulated in the models as having no tree cover.

Might the discovery of all of these trees actually lead to politicians taking less action against climate change? Because these trees supply them with a sort of excuse to do less to reduce CO2 emissions?

Our maps aren’t going to help solve the problem of climate change. So it would be short-sighted to use recently-discovered tree populations as try and say that things aren’t actually all that bad. After all, there are enough tree-planting programmes in the region – although they have more of a political than an ecological significance. We definitely shouldn’t keep chopping down the rainforest and trying to plant trees in the desert to make up for it. The biomass that’s present in the rainforest, with so many more and larger trees per hectare, is equivalent to about a hundred times that of the areas we studied. Despite that though trees in aris areas are very important, as they provide a livelihood for many people. And those trees must be protected against deforestation.

Do you have plans for future mapping projects?

We have now mapped an area ten times the size of that which appears in the paper published in Nature at the end of October 2020, and have reached about 15 billion trees. Our goal is to map all of the world’s arid areas within the next few years. That will also involve using data from so-called micro-satellites, which can image the entire Earth every day with a resolution of three metres. The results – exact coordinates, crown diameter and biomass of each individual tree – will be made freely available and is set to trnsform our understanding of arid areas.

Prof Dr Martin Stefan Brandt studied geography in Erlangen, received his PhD in Bayreuth and has been working at the University of Copenhagen since 2015. He works closely with the US space agency NASA, which allows him to use large amounts of commercial satellite data in his work.

This article is part of the RESET Special Feature “Satellites for Sustainable Development”. Click here to explore all of the articles in the series.

This is a translation of an original article that first appeared on RESET’s German-language site.