When it comes to the world’s oceans, none are seemingly more important to our planet’s health than the Antarctic Ocean. Also known as the Southern Ocean, the Antarctic Ocean is a huge carbon sink, with some studies suggesting almost half of all carbon uptake occurs within its famously frigid waters.

But as an important dampener to climate change, it is also highly sensitive to environmental shifts. Unfortunately for researchers, gaining accurate information in the unforgiving environment of the Antarctic is not exactly easy. Although research institutions have been established all over the continent, or in the southern reaches of other land masses, conducting long term oceanic surveys comes with a whole host of logistical, financial and safety concerns.

Luckily, there is an ample number of local ‘volunteers’ who have no problem diving into the freezing water: elephant seals. Institutions such as Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and the Sydney Institute for Marine Science have been experimenting for years with deputising these marine experts into their scientific research. And, as the waters across the globe warm and the conditions under the waves change, their work has become more important than ever.

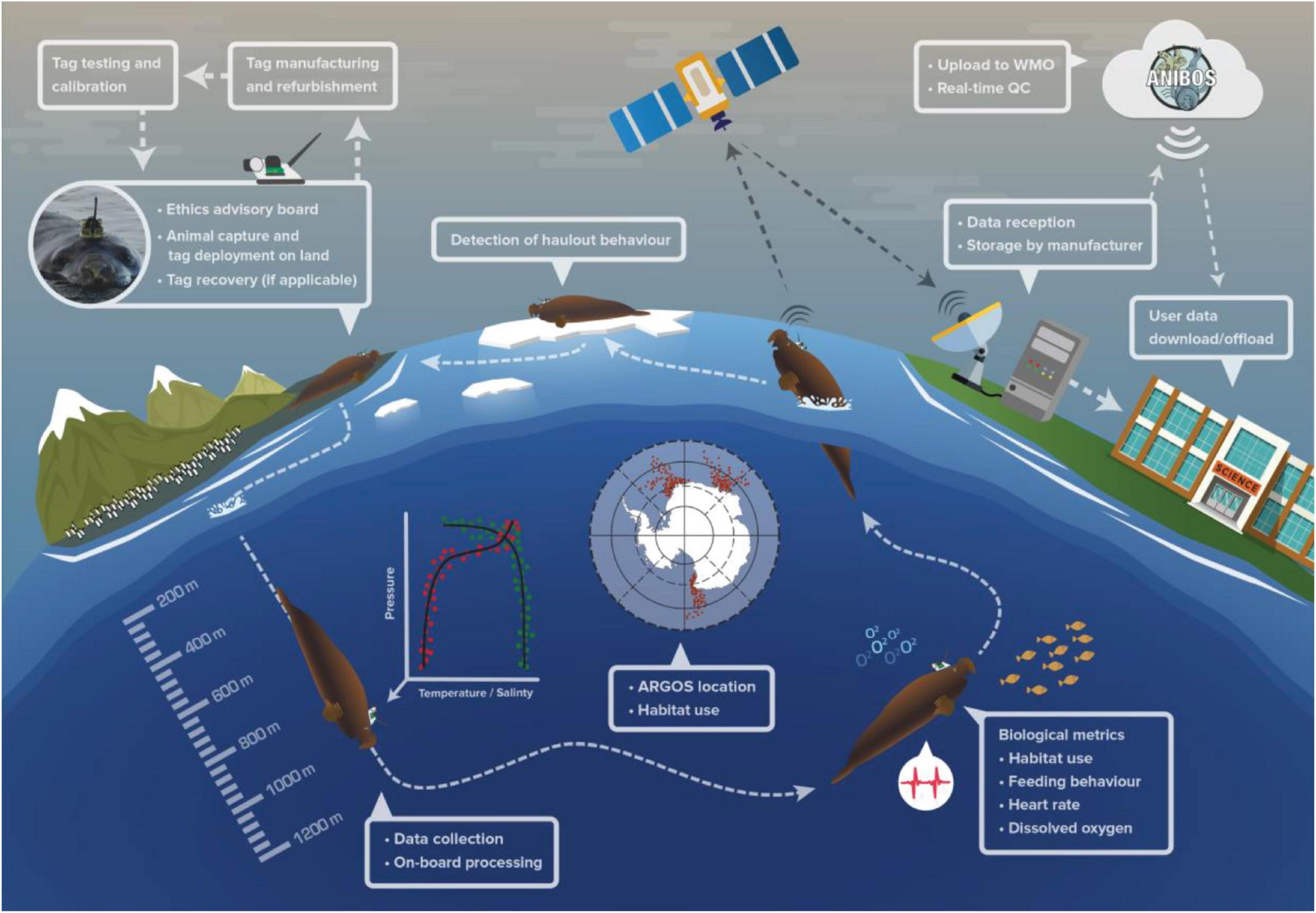

Of course, elephant seals are not always the most collaborative animals, and the application process for working with humans is slightly unorthodox. Researchers select specific elephant seals and then tranquillise them. Considering elephant seals can weigh in excess of 3,000 kilograms, this is essential for the safety of both the seal and their new human colleagues. Once sedated, a small electronic sensor is attached to the hairs on the seal’s head. The boxes are attached in January and February, following the moulting season, to ensure they stay attached for the longest period possible. Afterall, each sensor costs around 7000 EUR.

The whole procedure takes around 30 minutes, and GOOS is confident it causes no pain or distress to the animal. Indeed, once it reawakens, it begins going about its daily activities largely unaware of its new headwear.

Once attached, the sensors can provide constant updates about the conditions of the Antarctic Ocean, including temperature, salinity and oxygen levels. With elephant seals conducting up to 80 dives a day – sometimes to depths of 2000 metres – researchers can gain unprecedented access without the need for expensive submersibles or research vessels. Once the seal surfaces, the data is transmitted in near-real-time to satellites orbiting the planet where it can then be sent to researchers’ computers in, presumably, warmer and more comfortable surroundings. This can then be used to fill in gaps from other research equipment.

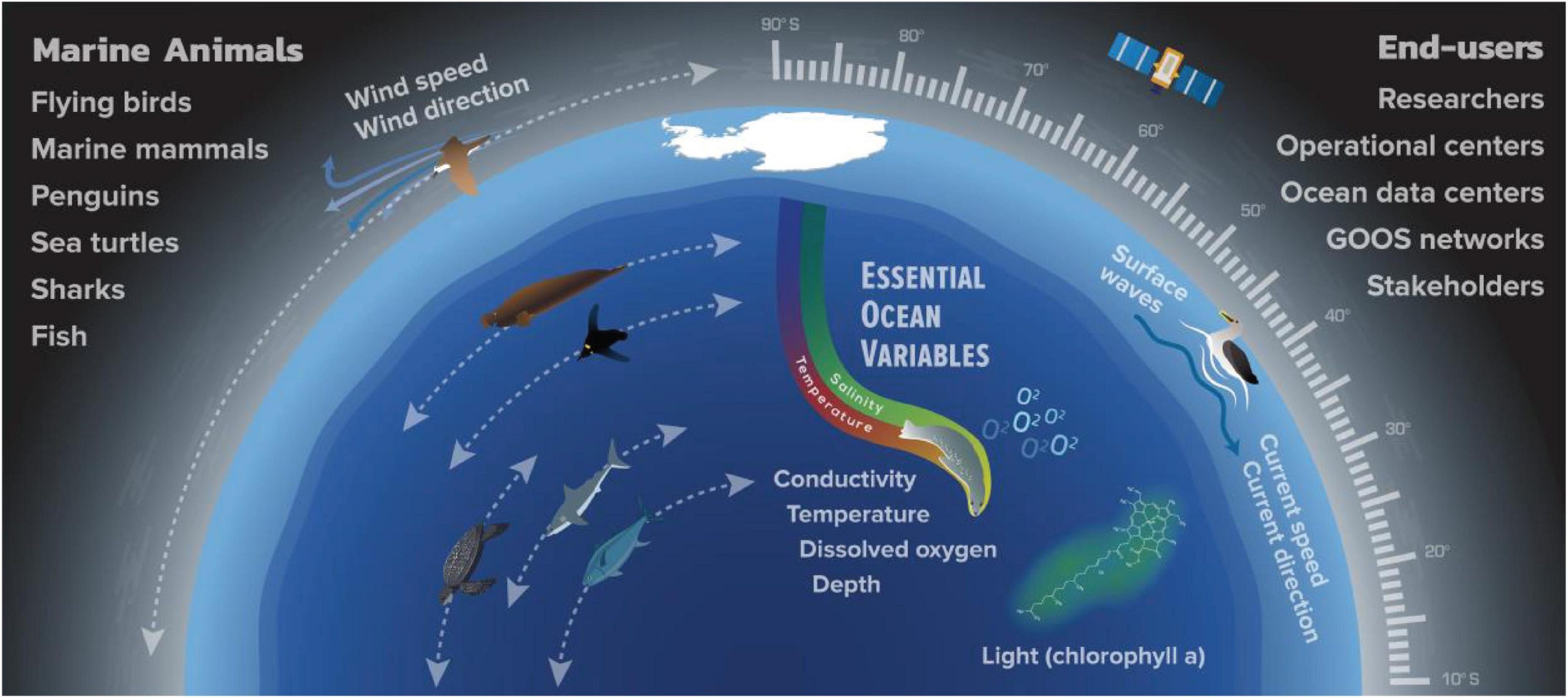

GOOS is now applying its expertise to developing the Animal Borne Ocean Sensors (AniBOS) platform which will provide a central home to all information gleaned by remote sensors attached to animals. However, it is not just elephant seals which have been brought into the project. Other species of seal, as well as turtles, sharks and seabirds also have their part to play. Each animal brings a different skill set to the research. For example seabirds can act as floating platforms, providing information about the surface of the water, while turtles, who travel large distances, can be used to record conditions in more tropical waters.

Even among seals there are variations. Some such as the Weddell seal are extremely deep divers but rarely move away from their home ice floats, making them better for in depth studies of a specific area. Meanwhile, crabeater seals are shallow divers but travel extensively around the Antarctic continental shelf, making them great for broader assessments. Overall, however, researchers have experienced the most success with elephant seals, with around 40 individuals being tagged for their studies.

A recent paper by the Sydney Institute for Marine Science and many collaborators goes into more detail about the achievements of the elephant seals. Their work has provided insights into a wide range of variables, including the formation of sea ice, Antarctic bottom water formation, ocean and ice shelf interactions, frontal system dynamics, and Antarctic mass water characteristics.

But what kind of remuneration do the seals get for their effort? Well, they also benefit from their labour, with the sensors also recording information about their lesser understood underwater lives, such as how, where and when they forage for food. Such information can also assist in conservation efforts to benefit the seals themselves.