A decade ago, it would have been impossible to create an accurate picture of the world’s fisheries. But advances in satellite technology, cloud computing and machine learning have made it possible.

Healthy oceans regulate our climate, are a vital source of food for around three billion people and provide a livelihood for millions. But unsustainable fishing methods take a heavy toll, destroying marine ecosystems and threatening food security as fish stocks dwindle. According to the FAO, 30 percent of commercial fish stocks worldwide are considered to be overfished.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include the goal of regulating fishing and ending overfishing so that stocks can recover. But even though many fisheries are already regulated, it is difficult to monitor what is actually going on in the vast expanses of the oceans – especially on the high seas, those areas beyond a country’s jurisdiction that cover almost half the surface of the globe.

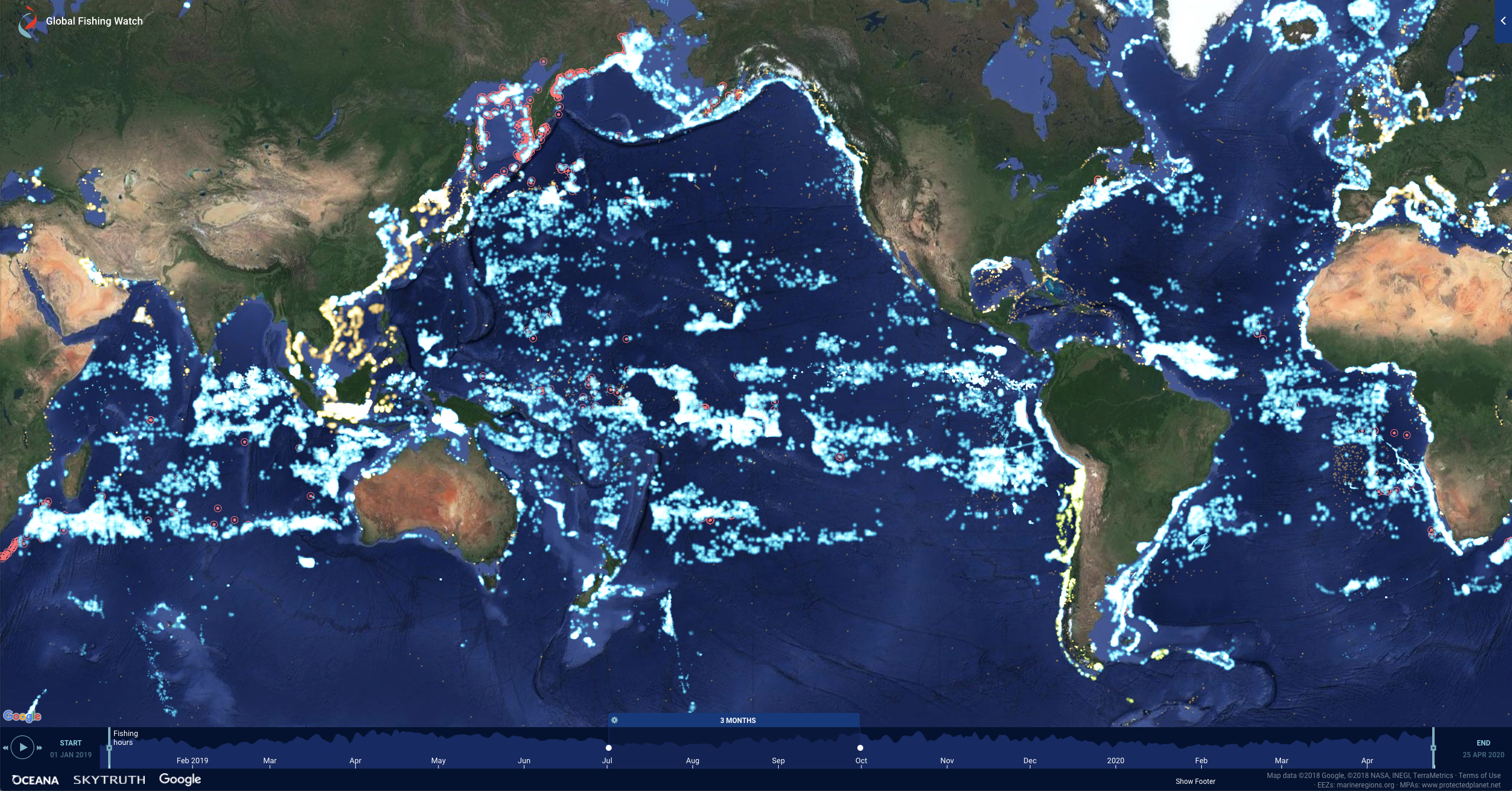

However, information on fishing activities is essential for effective, sustainable fisheries policy. The independent organisation Global Fishing Watch relies on satellite data to inform the public about overfishing in the world’s oceans and to make commercial fishing more transparent. To this end, Global Fishing Watch creates near real-time maps on which fishing activities can be tracked.

Using satellite images to make illegal fishing visible

An important source of information for Global Fishing Watch is the data collected by fishing vessels at sea. This includes the vessel monitoring systems AIS and VMS.

AIS (Automatic Identification System) data are unencrypted radio signals transmitted by vessels to avoid collisions and allow authorities to monitor vessel traffic. Each AIS message broadcast includes vessel identity, gear type, speed, course and position. AIS is mandatory on fishing vessels over 300 gross tonnes, so only a small proportion of the world’s approximately 2.9 million fishing vessels are equipped with the system – but they are responsible for a disproportionate share of the fish caught.

VMS (Vessel Monitoring System) is a satellite-based monitoring system for fishing vessels and is operated by individual governments. As the signals are encrypted, only the respective governments can access them. Currently, Global Fishing Watch receives VMS data from the governments of Indonesia, Peru, Panama and Chile through partnerships; further agreements with other national governments are being sought.

Global Fishing Watch also collects data at night, using a scanning radiometer called VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite), which is on board a weather and environmental satellite. Originally used for weather observations, VIIRS can detect the bright lights of vessels at night – and it also detects vessels that do not transmit AIS or VMS.

From this data, Global Fishing Watch creates livestream maps that are publicly available online free of charge. The interactive maps show at any time where and for how long fishing is taking place in fishing areas; illegal catches in protected zones can be made visible in real time. In addition, it is also recorded when ships switch off their AIS, for example to enter protected areas unnoticed.

For the first time, the extent of fishing is also made clear: the organisation’s analyses have shown that fishing covers more than 55 per cent of the ocean surface and is thus more than four times as large as agriculture in terms of area.

A key tool for effective conservation

Global Fishing Watch was born out of a partnership between Oceana, SkyTruth and Google. The independent organisation supports internationally recognised research institutions in gaining new insights into the complex challenges facing our oceans. The organisation also works with governments to better monitor and support enforcement of regulations. In 2017, for example, Indonesia became the first nation to provide Global Fishing Watch with its VMS tracking data, immediately putting 5,000 smaller commercial fishing vessels that do not use AIS on the map. This brings new insights into vessels fishing in Indonesian waters for longer than their allotted time or catching more than the legal limit.

But these data and visualisation tools could have an even greater impact: seafood suppliers and retailers can use them to check whether the goods they are buying come from legal and responsible boats. Researchers can use the data to identify vulnerable areas or evaluate the effectiveness of conservation and fisheries policies. NGOs and journalists can use it to advocate for greater protection of important ecosystems. And finally, fishing companies can use it to prove that they are working legally and responsibly.

However, the prerequisite for this greater benefit is, of course, that those responsible recognise the data and actually use these tools to implement effective measures.

This article is part of the RESET Special Feature “Satellites for Sustainable Development”. Click here to explore all of the articles in the series.