The European Space Agency has consistently been at the forefront of Earth observation technology, most notably with its Copernicus network made up of a variety of Sentinel satellites. ESA has now recently announced a series of contracts with aeronautic firms which hope to push this experience into a new generation, and on a previously unheard of scale.

On November 13th, ESA revealed it would be ordering six new Sentinel satellites to be developed and constructed simultaneously across the next decade. Currently, the space agency operates six Sentinel missions, each consisting of two satellites and altogether, an additional six missions have been planned for the future. The current missions cover a wide range of activities, including satellite imaging, mapping and atmospheric readings. The new generation of planned satellites, however, will be designed to take an even closer look at the world’s vital signs, especially those concerning climate change and the destruction of habitats.

The six satellites of the most recent announcements will be divided up into three new missions, dubbed CHIME (Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment), LSTM (Land Surface Temperature Monitoring) and CIMR (Copernicus Imaging Microwave Radiometer).

CHIME, which will be developed by Thales Alenia Space France to the tune of 455 million EUR, will be packaged with a hyperspectral imager that can better assess the health of crops and other plants from space. The LSTM mission, granted to Airbus Spain, will also be instrumental in monitoring agricultural conditions. Its infrared thermal sensor can measure land surface temperature and could be used to predict droughts.

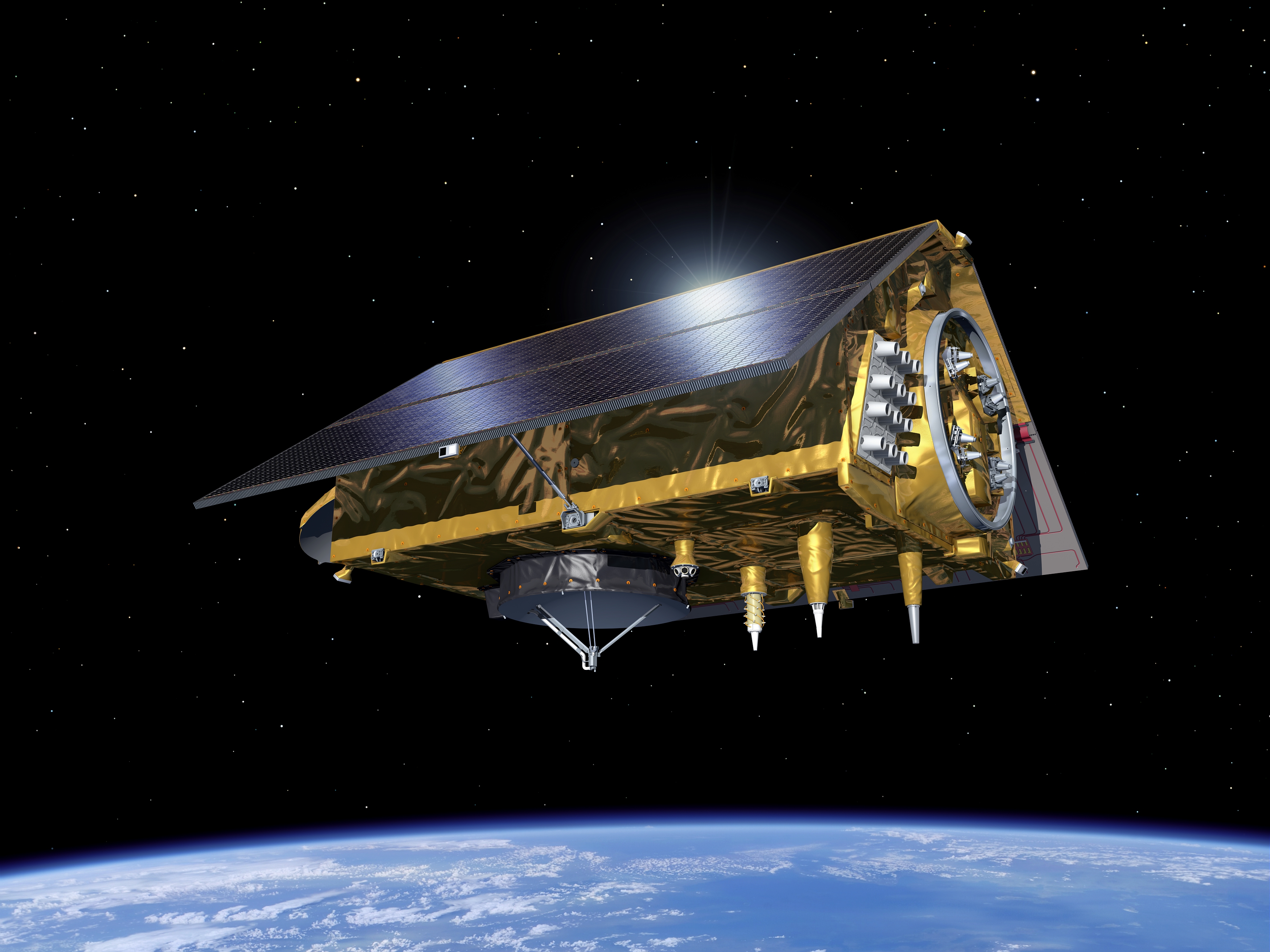

The CIMR mission, awarded to Thales Alenia Space Italy, will contain a suite of microwave radiometer tools which can measure sea-surface temperature and salinity. This will work in tandem with other Sentinel missions to monitor ice cap density and overall sea levels.

In recent years, satellites have become instrumental in the large scale acquisition of information to fuel research and policy into environmental protections. The ESA’s Sentinel programme provides all of its readings to international researchers free of charge and without limit, however it has also been joined by many commercial and non-governmental agencies using satellite technology for good. Indeed, over the last several months, RESET has been looking closely at how projects involving satellites can be used for a wide range of activities, including wildlife monitoring, supporting humanitarian missions and maintaining corporate accountability.

Too Much Too Soon?

One key advantage of satellite technology over traditional research methods is its ability to provide a broad overall of climatic conditions. Previously, in situ methods of information gathering, such as the use of research vessels or sensors, were used to gain the same readings now provided by satellites. Although this may be more accurate on an extreme local level, it is often difficult to see how such readings fit into a global and connected ecosystem and atmosphere. Satellites provide this ability, with increasing accuracy, and without the added logistical effort, which is especially beneficial for smaller, non-profit actors.

Launching dozens of high-tech satellites into space, however, does not come cheap and despite the recent announcements, Sentinel’s future is not fully guaranteed. Currently, the projects are funded until the end of next year, when ESA and European Commission officials will gather to assess the finances in detail. If they do not seem cost effective, some of the missions may be scrapped or scaled back.

Although the ESA’s Copernicus programme has previously been overfunded by member states, who were often eager to pursue the research and strategic potential of Earth observation technology, this year’s budget is looking a little slimmer. Currently, according to the latest estimates, the project has been earmarked with 4.8 billion EUR by member states, around 2 billion less than desired. In this sense, it’s unclear if, or how, all of Sentinel’s proposed missions will make it into space. It is hoped British reentry into the programme with a post-Brexit trade deal may provide the funds needed, but this might also be currently overly-optimistic.

Despite this lacklustre response – perhaps partly due to member state insecurity regarding the ongoing coronavirus pandemic – the Copernicus programme is still expanding. On November 21, Sentinel 6-A will take off in conjunction with Space X, where it will kickstart a new mission designed to accurately gauge the depths of the oceans across the globe.