The CO2 emissions of our buildings are high, accounting for around 36 percent of the EU’s total emissions — far too high to bring our climate targets within reach. But there are ways and means to achieve climate-neutral buildings, and people who are working intensively on this. One of them is Sibyl Steuwer. She heads the office of the Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE) in Berlin.

BPIE, a non-profit organization founded in 2010 and based in Brussels, operates as a think tank focused on climate protection within the building sector. A primary mission of BPIE is to provide scientific support for the implementation of the Buildings Directive across EU member states. To accomplish this, their team conducts comparative analyses, assesses national initiatives aimed at climate protection in the building industry, and offers guidance to policymakers and other influential decision-makers. Furthermore, BPIE is dedicated to advancing sustainable construction practices and fostering the creation of healthy living environments.

We met with Sibyl Steuwer and talked to her about the levers we have at our disposal to transform the building sector. We also asked her in which areas digital technologies can be effective.

The building sector accounts for 40 percent of total CO2 emissions in Germany and the figures for Europe are similar. Where do you see the biggest opportunities for reducing these emissions quickly?

In the short term, we need to focus on the building stock and reduce emissions from the operation of buildings. This requires concrete targets and requirements and, in my view, also regulatory law. In recent years we have seen that the available information and financial support do not provide enough incentive to accelerate investment cycles.

So it’s about being very clear about where we want to refurbish our building stock to make it fit for the future. And then it’s about refurbishing the most inefficient buildings first, partly to create a better living environment and to protect residents from rising CO2 prices. Because it’s clear that we will continue to have rising energy costs, and I think that’s how it has to be communicated.

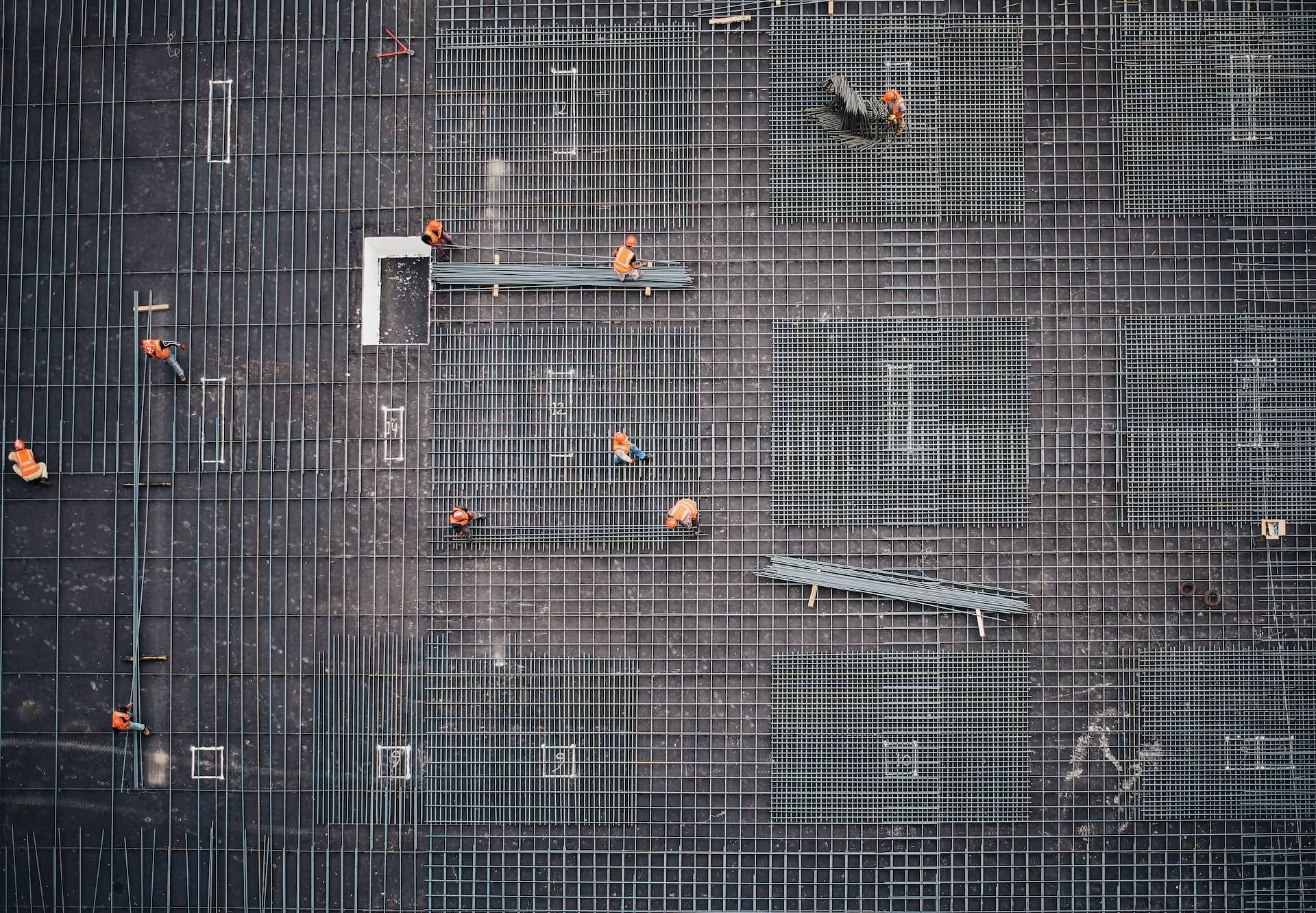

We definitely need to reduce energy demand and make our heating system renewable. The first steps have now been taken with regard to the latter. But it’s also about reducing demand, and that means we have to refurbish the building envelope. The necessary skilled labour is already barely sufficient. This means that labour productivity must at least double so that the refurbishment rate can also be doubled. Therefore, we need innovations and new processes to accelerate refurbishment and to really do what is necessary with the skilled workers we have. Serial refurbishment is one option.

Serial Refurbishment

Serial refurbishment involves the prefabrication of façade, roof elements, or system technology components, such as heat pump modules, off-site before they are assembled on-site. This approach significantly reduces the time needed for renovation compared to traditional methods, thanks to the extensive prefabrication involved.

What are the possibilities for increasing efficiency in refurbishment?

Standardising processes is crucial. This entails keeping processes consistent, even when dealing with unique buildings. In the construction industry, where trades are often commissioned individually, there is an increasing emphasis on integrating planning, construction, and operation. This approach allows for learning from each phase and better optimisation, leading to improved coordination of processes.

A continuous digital process is incredibly beneficial in this context. Think of it as having a model that provides all the vital information, aiding in planning the refurbishment process from the outset. Ideally, there should be a solution provider who plans everything comprehensively and then implements it alongside various trades.

Greater standardisation can save significant time and resources, and I believe this is how futurerefurbishments should be approached.

Another aspect is maximizing off-site manufacturing and increasing automation, relying more on robotics. The concept here is to assemble less on the building site, focusing on attaching facades and performing manual finishes. Through prefabrication, we canrefurbish more swiftly and refine our processes. However, we still have some way to go in achieving this goal.

When it comes to refurbishing existing buildings, we often encounter highly individual structures. However, there’s also a clear need for standardised procedures to expedite the renovation processes. How can these two aspects be better integrated, and what role can digital tools play in this endeavor?

For instance, with a digital twin of the building, you can tailor your plans and explore various solutions for individual cases. Admittedly, creating the digital twin is an initial step, but it’s the direction we’re heading in for the future. This means that once we’ve digitally surveyed the building, understanding its characteristics and identifying the optimal solutions, we can manufacture with great precision in a factory setting while still adhering to standardised processes. Such initiatives are already being put into practice through various pilot projects today.

You said that more guidelines are needed so that more companies move towards serial renovation. But what else needs to happen to promote sustainable construction and more efficient buildings?

An important sticking point is the building regulations of each state. In their current form, they prevent many innovative developments. The other is the question of how contracts are awarded. This starts with public procurement law. Many municipal housing associations put trades out to tender individually. This makes serial renovation and offering solutions from a single source difficult. Planning, construction and operation are thus completely separated. This means that it is a matter of establishing an overall contra ct award as a standard procedure.

There are good examples from the Netherlands, where serial renovation originated. There, a performance guarantee is granted at the end of the refurbished product. This means that the solution provider who plans everything assumes the guarantee that the corresponding energy savings will also be realised through the refurbishment. It is possible to think in leaner terms, but the fact that a certain performance is guaranteed, for example over 30 years, has implications for how such a refurbishment has to be organised and ultimately affects the entire value chain.

In order to minimise the risk on the entrepreneurial side, state support was decisive in the Netherlands. You simply have to find solutions that have perhaps not yet been established.

Buildings are a CO2 heavyweight: the construction, heating, cooling and disposal of our homes accounts for around 40 percent of Germany’s CO2 emissions. We will only achieve our climate goals if these emissions are massively reduced.

But how can we achieve the sustainable transformation of buildings and what role do digital solutions play in this? The RESET Greenbook provides answers: Building transformation – intelligently transforming houses and neighbourhoods.

We’ve previously discussed the use of digital technologies in the context of optimised planning processes. However, there is now an increasing number of buildings in which energy consumption is to be optimised with various technologies. What are the opportunities in this regard?

The way I see it, not every technology is always useful. Because when I install something, it is also susceptible to damage. You have to look at the individual case; sometimes it makes sense to optimise with the help of digital technologies.

But I think it can make more sense in renovation than in new construction. I’m rather critical of designing completely smart buildings, especially because the buildings could be planned much better from the outset, as we have a lot of information about life cycles and emissions. With the help of bio-based building materials, you can also cool buildings, for example. This means that a lot is possible through the choice of materials, and we simply have to think about it much better.

You mentioned some examples where digital technologies play an important role at the beginning of a building’s life and in its operation. However, the high emissions, amounting to 40 percent, are the sum of all emissions over the entire life cycle. Can new technologies also support sustainability at the end of a building’s life?

Yes, at BPIE, for example, we are strongly committed to a digital building logbook in which, among other things, energy performance certificates, the plans of the building and the materials used are stored. All available information can be brought together in this way and is then available digitally.

Knowing which materials are used is not only important for renovation, but also for the recycling and disposal of buildings at the end of their life cycle. For this we need data, and currently we have a poor overview of our building stock, of our consumption, of the building materials used. This is being improved step by step, but we don’t know exactly where which buildings really are and what their performance is.

For new buildings, we definitely need to make sure that we record which materials are used and introduce and consistently maintain a building resource passport. A compulsory introduction for all new buildings as well as for far-reaching renovations should be possible without any problems before the end of this legislative term. In the case of refurbishments or conversions, this means carrying out an inventory of building components in order to systematically record and digitise the existing building stock and to be able to reintroduce materials from the conversion. The inventory gives a clear picture of the urban mining potential and should be introduced step by step starting with public owners of existing buildings.

The digital building resource passport already exists, doesn’t it?

Yes, there are private initiatives and companies that offer various building resource passes. You pay something and can then use a building passport. This way, owners can understand exactly which materials and volumes are used, so that they can really reuse them later. Theoretically, this can also be done by inspecting existing buildings, measuring and assessing them, and then recording the new materials used during renovation.

In the private sector, there are various approaches that think about this in different ways. Some providers focus more on the inventory of materials, others focus more on the optimisation and automatic creation of a renovation roadmap, whereby the data can also be used when recycling or disposing of the building.

There are good examples from the European member states. In Flanders, all owners get an ID for their buildings with which they can log into their digital logbook on a central platform. The energy certificate and other building and environmental data are then stored there. Even the connection to public transport can be read here. The owners can then decide whether they want to share the information and which data they want to add. For example, if a renovation is planned, the companies can access it if the owner allows it.

Are you optimistic that a uniform building passport will be introduced in Europe?

In the RenovationWave Strategy of the EU Commission, there is an action plan within which the introduction of a digital building passport is planned for 2024. This does not yet mean that it will automatically be directly available in every member state. But if we look at the political level, we see that the willingness to set certain requirements for new buildings is changing and that the supporting measures for this are also being developed. We see a clear trend towards setting sustainability criteria for buildings in order to really optimise them in the planning and design stages. Nevertheless, we are only at the beginning. In order to achieve the climate goals, the necessary policies and measures must now be put in place quickly. Climate change is not negotiable.