Exmouth Leisure Centre has a gym, sports classes and a 25-metre pool where locals come to swim laps. So far, nothing unusual. But beneath the swimming pool lies a 50-kilowatt data centre. Roughly the size of a chest freezer, it generates heat as it stores and processes data. This heat is then used to keep Exmouth’s swimming pool warm.

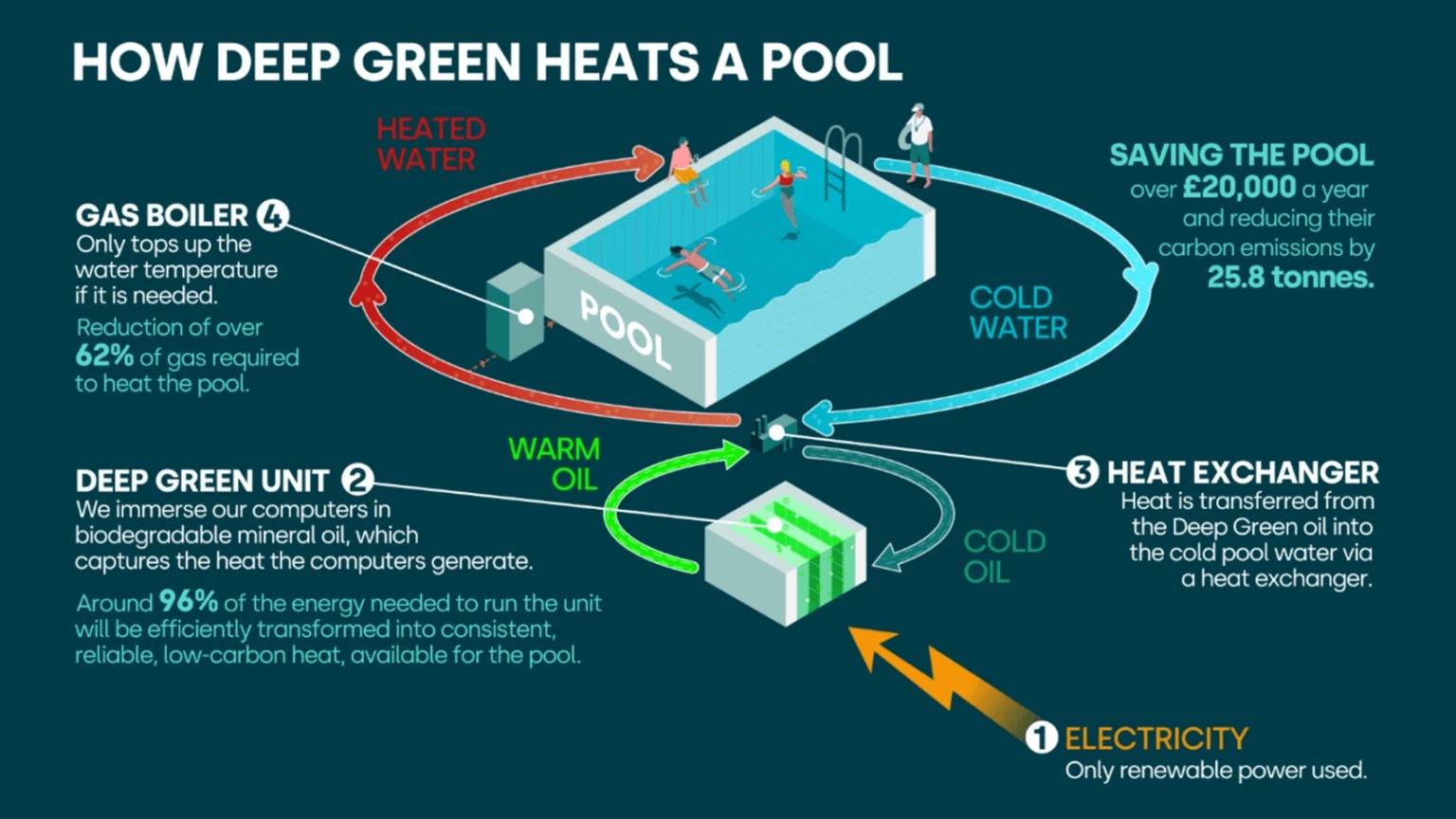

Matt Bagwell, Chief Marketing Officer at Deep Green, the company behind the data centre, describes this as the “perfect symbiotic relationship.” Swimming pools need heating – many are struggling to keep up with bills as energy costs soar – and data centres will produce heat wherever they are in the world. By installing a data centre beneath a swimming pool, Deep Green calculates that they save leisure centres such as Exmouth over £20,000 a year and reduce their carbon footprint by 25.8 tonnes.

As AI models become increasingly prevalent, our energy consumption will only increase, with Scientific American reporting that by 2027, the annual electricity consumption of AI servers will be greater than that of many small countries. But this creates a problem: data centres cause a lot of carbon emissions, with both the data processing and the cooling of servers responsible for this high energy consumption. There are a variety of startups tackling the problem of what to do with waste heat. In Sweden for example, the waste heat from data centres is being used to heat thousands of households, and in Germany, Windcloud uses heat from servers to warm a greenhouse which grows algae.

So how does waste heat from servers actually work?

The data centre from Deep Green is immersed in biodegradable mineral oil, which captures the heat the computers generate. A heat exchanger transfers heat from the oil to the water of the swimming pool, making it an ambient temperature perfect for bathers. The swimming pool’s existing gas boiler is only used when necessary to maintain this temperature.

Data centres are responsible for a lot of the planet’s pollution

Climateiq reported that data centres generate more emissions than the aviation industry, while Deep Green calculated that the world’s data centres collectively consume half as much energy as the whole of Germany. But Bagwell describes how, outside of this industry, people rarely expect climate emissions to be so high from something we cannot physically see.

He gives an example: when you open TikTok or Instagram on your phone, how often do you consider the carbon emissions that come from your scrolling? “When we’re disconnected from something, we tend to do damage to it,” he continues, emphasising the need to understand the environmental impact of the online world.

Swimming pools get their heat for free

Deep Green currently has over 40 megawatts in planning stages – and they intend to heat swimming pools around the U.K. without it costing the leisure centres a penny. Not only does Deep Green provide the heat generated by its data centres for free, but it also covers the costs of installing its technology, instead earning profits by selling storage at their servers to companies requiring computing.

RESET asked Bagwell why their business model is structured like this. “Public assets like swimming pools need to stay open for people’s [mental and physical] health,” he says. “There’s a direct causal relationship between the availability of public assets like swimming pools and health outcomes.” In 2022, the BBC reported that 79 percent of leisure centres faced closure due to rising energy bills – for many of them, Deep Green’s innovation is a lifeline.

The reaction from leisure centres has been positive

“Initially our conversations are very attractive,” Bagwell says of that first call with a swimming pool that may soon host a data centre. But soon they get into practicalities. Deploying a data centre takes just three days; planning can take months. Despite this, countless swimming pools still want to get in on the scheme; after the launch of the first data centre in Exmouth, Deep Green was inundated with requests.

In numerical terms, Deep Green aims to expand to 1500 sites in the U.K., saving leisure centres £80,000 in heating bills and 125,000 tons of C02 per year. But Bagwell explains how “it’s not about the ones and zeroes.” Deep Green’s ambitions are higher than that; they want to “become a beacon of hope” and change how people feel about climate change, energy bills, and the cost of living crisis. As Bagwell puts it, “When you change heat economics by giving heat away, the whole game changes.” It becomes a game we might just win.