Monocultures, compaction and rising temperatures — our soils will offer significantly poorer conditions for agriculture in the coming years. It is therefore essential that farmers protect their soils better to maintain their fertility. Smart monitoring could provide farmers with the information they need.

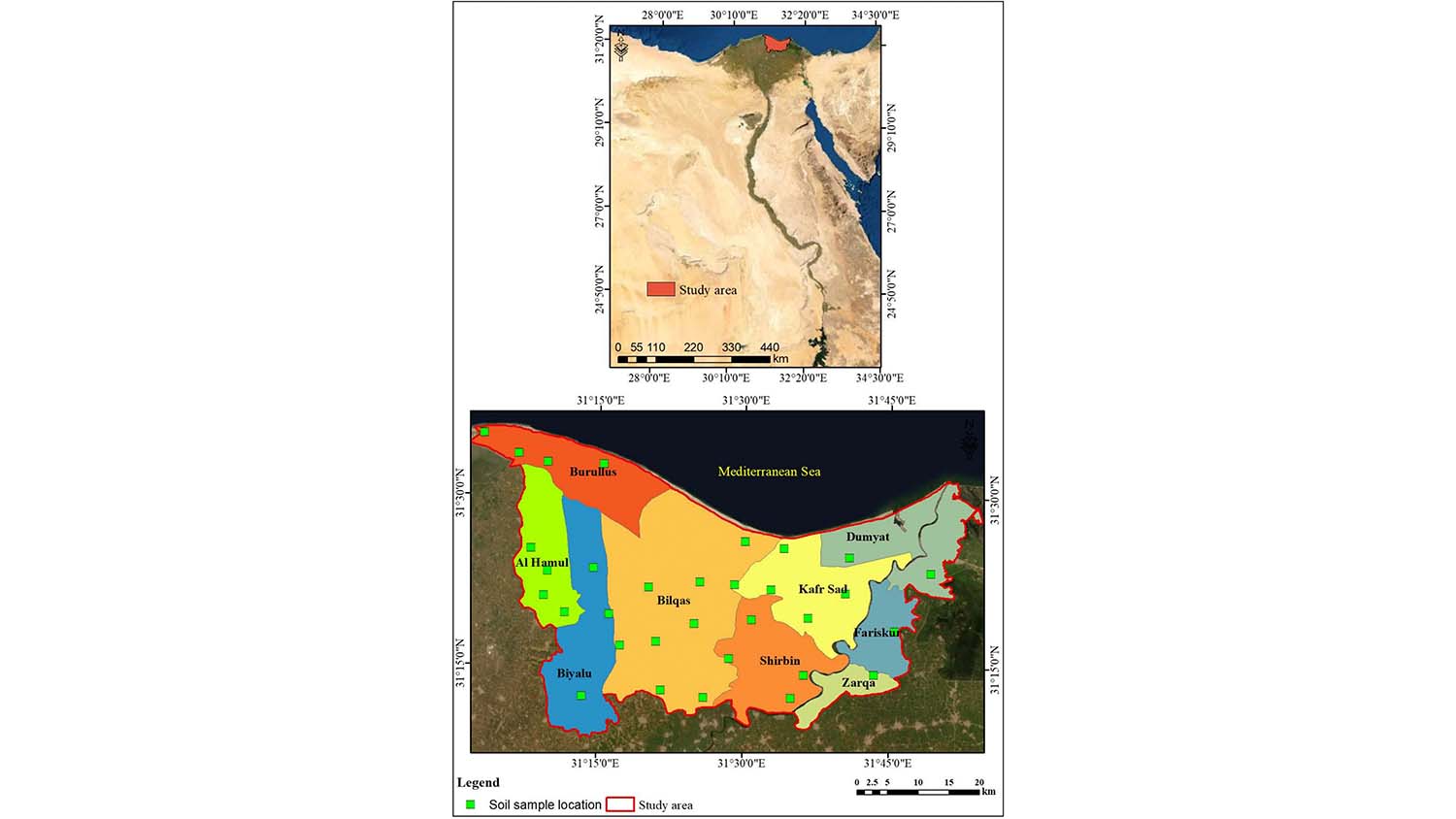

A project at Benha University in Egypt demonstrates the possibilities that smart soil monitoring can offer for the future of agriculture. The researchers focussed on GIS data, using machine learning to calculate the soil quality of a huge area in the Nile Delta.

Protecting the ground with maths

Measuring the soil quality of a 2,300 square kilometre area using conventional methods is a mammoth project. Using conventional methods, researchers would have to scour the entire area, collecting enough samples to obtain just a rough map. In contrast, the researchers at Benha University were able to calculate soil quality in the Nile Delta using data from just a few samples.

32 soil samples up to 30 centimetres in size were taken from various locations along the Nile Delta. Their chemical and physical properties were then analysed in the lab, before being combined with preexisting data from a geographic information system (GIS). The researchers were then able to draw conclusions about the soil quality of the entire area from the samples.

What is a geographic information system (GIS)?

A geographic information system (GIS) is a computer system used to capture, store, check and then display data related to positions on Earth’s surface, such as streets, buildings and vegetation. GIS allows users to better see, analyse and understand patterns and relationships between these items.

The data, which was interpolated using mathematical functions and algorithms, provided specific recommendations for action in areas with poor soil quality.

For example, in order to improve soil quality in the area under investigation, the recommendation was made to plant more salt-resistant plants and prevent soil leaching with the help of water drains. The method could also be used to test whether the measures actually impact soil quality in critical areas.

If such measurement methods become established, we will be able to monitor soil quality much more easily in the future. Permanently placed sensors at a few locations could then provide regular calculations of the environmental needs of an entire region. However, researchers see even greater opportunities for consistent monitoring.

Modern sensor technology is a great opportunity for agriculture

The Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) proposes an “Environmental IoT” for effective monitoring. In other words, a network of sensors, smart agricultural robots and other devices connected via the internet. Additionally, the “prediction of soil properties using a combination of nanosensors and machine learning could support the preservation of soil quality”, similar to the approach taken by the Egyptian researchers.

Smart monitoring can also be used to improve the understanding of interrelationships and ecosystem services on agricultural land. High-resolution sensors can support the classification of habitats, for example, based on which biodiversity can be modelled. And, if land management and the application of agrochemicals are then adapted to the conservation of ecosystems, consistent monitoring can serve to protect species. If the places where birds and insects can be found are known, targeted measures can be implemented to protect them. This in turn leads to the preservation of plant biodiversity and better soil quality.

Also exciting: fawn rescue using drones

The BfN also mentions the rescue of fawns as a use case for monitoring technologies. Drones equipped with thermal imaging cameras are to be used for this purpose.

The aim is for farmers to use these to recognise fawns before they mow lawns.

A similar idea is being pursued by researcher Paula Meyer, who wants to improve the coexistence of bears and humans through mapping.

However, data collection and analysis with regard to biodiversity indicators is still in its infancy. Digital technologies are increasingly being used in agriculture and all the sensors, drones and management systems are collecting a wide range of data. However, these are primarily used to optimise processes with the aim of reducing costs for farmers and increasing yields. Data that allows conclusions to be drawn about biodiversity and the wider context of ecosystems is more of a by-product. This makes it all the more important to promote applications in this area and make the data available for targeted environmental protection measures.

Their risks should not be ignored.

Problem: Data sovereignty and monopolisation

Agricultural data, with its combination of location data and information from environmental analyses, is extremely sensitive. In order to be used effectively, however, it should be available to as many farms and companies as possible. However, the data often remains with the providers of agricultural software and it remains unclear whether and how it is processed and passed on.

This is why the anonymisation of personal data and open interfaces should be taken into account when developing digital solutions, as Dr Sonoko Bellingrath-Kimura emphasises in an interview with RESET. This is an “essential point in order to achieve the necessary networking” and then “everyone can use and develop it, regardless of whether they are large corporations or start-ups”.

The data should also belong to the farms so that they can decide where the data flows go. Currently, clauses on automatic data flows in contracts for the purchase of sensors and machines often lead to farmers being sceptical about new technologies.

Artificial intelligence can make monitoring even more efficient

Such framework conditions will be particularly important if the agricultural revolution is to benefit from the current AI boom. The start-up Hortiya is already demonstrating the possibilities of “plant AI” at the greenhouse level. Using sensors and a “language model of the plants”, the application can draw conclusions about the status of tomatoes, basil and cannabis. This makes it much easier to assess the needs of the plants.

Systems that work with artificial intelligence and machine learning are particularly good at recognising correlations between a wide range of data. As the network of sensors and machines grows, so agriculture monitoring is driven forward. The Federal Office of Food and Agriculture is therefore promoting the development of AI systems in agricultural contexts. According to the BMEL, the potential ranges from optimising the use of water, pesticides and fertilisers to shortening supply chains by better networking in urban and rural areas.

Monitoring is a great opportunity — if the framework is right

We can therefore already estimate the potential of consistent monitoring in agriculture very well today. If we set up an “Environmental IoT” in agriculture, as the BfN calls it, we can better recognise connections between agricultural decisions and their impact on the environment. At the same time, this would make it possible to react more sensitively to the requirements of flora and fauna and to monitor the effectiveness of protective measures.

However, the establishment of such a network requires a political framework to protect companies and offer them added value in the acquisition of such technologies. It is also important to make the data accessible to all stakeholders.

Agriculture is facing major challenges: On the one hand, it is severely impacted by biodiversity loss and the effects of climate change. On the other, agriculture itself massively contributes to these issues.How can digital solutions on fields and farms help to protect species, soil and the climate?

We present solutions for a digital-ecological transformation towards sustainable agriculture. Find out more.

How can digital solutions on fields and farms help to protect species, soil and the climate?

We present solutions for a digital-ecological transformation towards sustainable agriculture. Find out more.