Remote sensing is quickly becoming the backbone of climate and conservation research, as well as the next generation of agriculture. By placing sophisticated sensors around an area of interest, researchers and others can gleam reams of important information without needing to be permanently in the field.

However, although sensors can greatly reduce logistical burdens, they are not entirely free from them. The locations for sensors must be selected, and then the equipment installed. Some may require more bulky technology, such as large batteries. Placing such sensors takes time, while manpower and costs may limit the amount of sensors that can be practically used.

A research team at the University of Washington has been exploring methods of creating mass sensor networks quickly and conveniently. To realise their goals, they took inspiration from the humble dandelion.

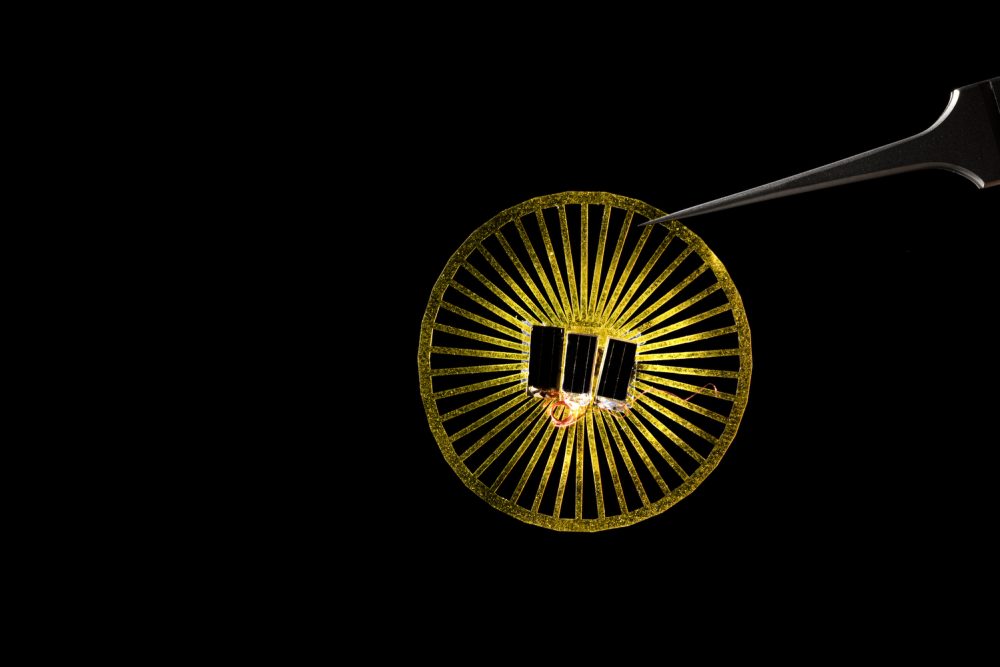

Dandelions have become hated weeds for many farmers, and the key to this sour relationship is their ability to spread their seeds over relatively vast distances. By mimicking the light tendrils (or pappus) of a dandelion seed, the team has created environmental sensors that can be dispersed into the wind across a wide area..

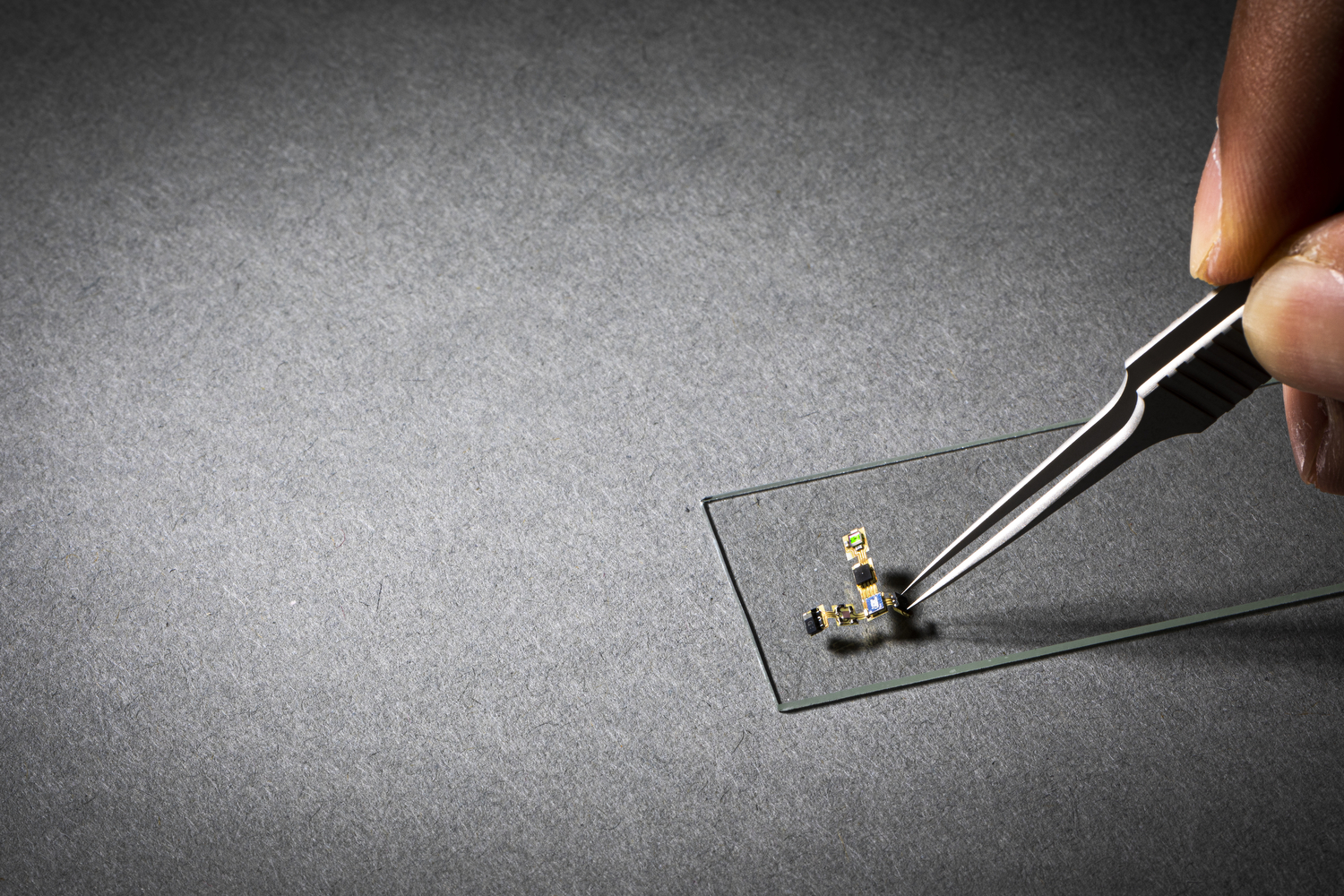

The sensor they have developed is about 30 times heavier than a 1 milligram seed, requiring its ‘pappus’ to be larger and more rigid. However, the sensors can still travel an impressive distance even on a moderate breeze. Testing on the university campus has shown that the dandelion sensors can float up to 100 metres from their release point. Varying the height of the release point, affects the distance travelled. Once on the ground, the device, which can hold up to four separate sensors, can gather information from within a 60 metre radius.

The idea would be to release these sensors, for example from a drone, to rapidly establish a sensor network over areas the size of a football field. Senior author of the study, Shyam Gollakota, a UW professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering stated:

“We show that you can use off-the-shelf components to create tiny things. Our prototype suggests that you could use a drone to release thousands of these devices in a single drop. They’ll all be carried by the wind a little differently, and basically you can create a 1,000-device network with this one drop. This is amazing and transformational for the field of deploying sensors, because right now it could take months to manually deploy this many sensors.”

Sensors on the Wind

To keep the weight down, the team experimented with over 75 different designs to find the one which kept the ‘terminal velocity’ – or maximum speed of which the sensor fell – to a minimum. Additionally, the sensors do not use batteries, instead they are powered by small, lighter solar panels. However, This approach does create some additional challenges. The panel needs to land the right way up to charge the device, while the sensors cannot function at night. Luckily, the sensors are specifically designed to flip over to the right orientation, meaning 95 percent land the correct way up.

A lack of battery also means the sensors need more power to start up in the morning. To partly overcome this issue, the sensor includes a capacitor which can store a little charge overnight.

Once in position and charged, the sensors can gather information concerning temperature, humidity, pressure and light, which is wirelessly sent back to researchers via backscatter, a method of sending information by reflecting transmitted signals.

But, the design still needs to be refined. Currently, the team is also looking at altering the shapes of individual sensors to create more variation in travel distance and pattern, meaning the sensors will become more widely dispersed. Once again, the team has taken direct inspiration from nature. Co-author Thomas Daniel, a UW professor of biology explained:

“This is mimicking biology, where variation is actually a feature, rather than a bug. Plants can’t guarantee that where they grew up this year is going to be good next year, so they have some seeds that can travel farther away to hedge their bets.”

Eventually, it may even be possible to create sensors that can move around once they hit the ground, allowing them to get even closer to specific areas of interest.

However, there is one major downside to this approach. With such a large number of sensors being spread over a wide area, it will almost be impossible to retrieve them all. Their lack of battery means they can continue to function long term, but the team is also looking at ways of making the sensors more biodegradable.

In recent years, sensors have taken on an increasingly important role in scientific and environmental research. However, their utility is not limited to universities and other research institutions. The drop in cost of sensor components has led to a surge in citizen science projects, in which normal people donate their time and effort to help conduct mass research. Much of these citizen science projects also ties into themes of civic technology, a topic RESET covered at length in our last Special Feature.