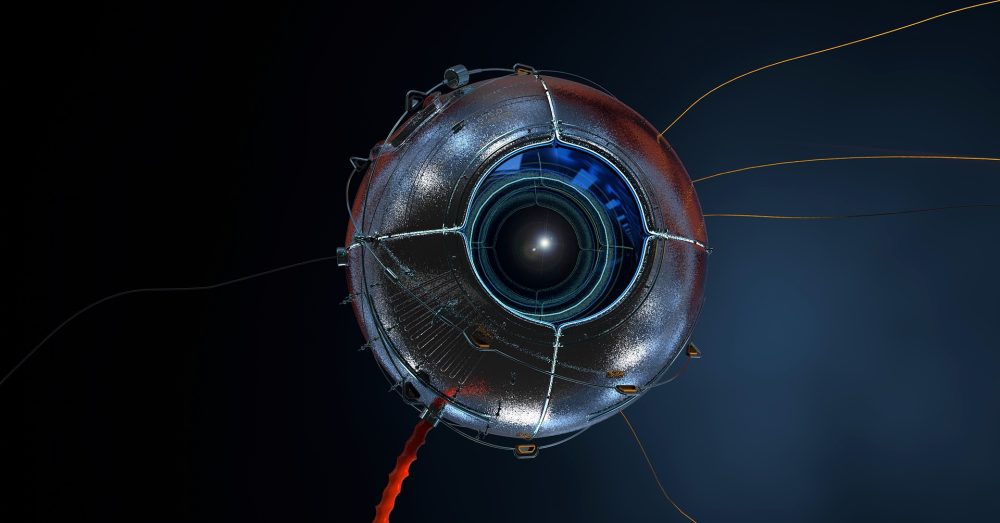

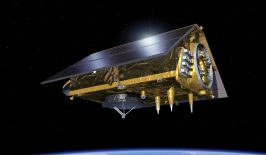

Thousands of satellites are orbiting our planet right now, and their number is increasing at breakneck speed. These spacecraft are able to monitor every corner of the Earth, making images with ever-higher resolutions. Private satellite companies are already taking 30cm VHR (very high resolution) images. It’s technically even possible to take 10cm resolution images. It is true that at this point in time and with the current technology, it is probably not yet possible to identify faces – but is this really the question that matters when it comes to data protection?

Probably not. Because in the digital age, even lower-resolution satellite imagery can be personally identifiable – namely, when various data points are linked to form information. And as the quality of data sets increases, with near real-time monitoring from space and increasingly powerful AI systems capable of correlating, analysing and interpreting vast amounts of data, it becomes increasingly important to evaluate remote sensing technologies from a privacy perspective.

In this in-depth interview, we speak to data protection expert Marit Hansen about the extent to which satellites and also drones are problematic in terms of data protection, what risks and potential for misuse there are wwith remote sensing data – and how we can help ensure that the data collected is used for good.

The computer science specialist has been the State Commissioner for Data Protection in Schleswig-Holstein since 2015 and is concerned, among other things, from a technical and legal perspective with how to implement data processing that complies with fundamental rights. She is also a member of the Federal Government’s Data Ethics Commission and a member of the Advisory Board on Employee Data Protection of the German Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

To what extent does data protection play a role when it comes to satellite imagery?

The question is: Are satellite images personal or not? When it comes to data protection, this is the first question, because the focus here is on personal data. However, while this sounds as if the issue of personal data is binary – i.e., either the data is personal or it is not, either data protection law applies or it does not – the issue is dynamic. It is becoming increasingly apparent that a great deal of data has the potential to be personal. Perhaps there is data that does not currently give that impression, but if I collect further data and information and link them together, then it may be possible to draw clear conclusions about a particular person. You can often get an amazing amount out of just a few data points.

So even if a satellite company doesn’t specifically collect such data and isn’t even interested in it – a third party with further insights could later bring these points together so that, for example, a person’s movement patterns could be tracked. Mind you, for now the resolutions are usually not high enough for us to be able to recognise individual faces, for example – but you often don’t have to do that, as further information is also sufficient for the images to be relevant for third parties.

What kind of information might that be?

For advertising purposes, this could be, for example, the information that there is a swimming pool at a certain address. Then you might get an offer from a service provider to clean the pool. But of course, you could also conclude that someone with a swimming pool is probably wealthy – in which case it might be worth breaking in. And with the right data, you could also plan the escape route. These are all things that are not super-secret, but are more or less publicly available. But it’s the way they are put together that opens up new possibilities. Today, an enormous amount of data is collected, for example via location-based services in our smartphones or via surfing behavior. Where does a person work, what are they interested in? This information can be relevant for assessing creditworthiness, but also for law enforcement, for advertising, and also for manipulation. It is possible that this data could be used against people. In this context, with this huge potential for risk, satellite data would constitute a small building block. It would add more data, and certain situations that previously seemed unimportant would have to be reevaluated.

Until now, data protection hasn’t been a big concern for remote sensing imagery. But it seems like that’s about to change.

True, we have an area here that is very much in development, with ever better sensing technology, with ever more data sources, ever more data that is being shared. On the one hand, that can be very beneficial for the common good. But it is important that the risks are always considered as well. I’m not saying this as a pessimist, but as someone who is trying to shape the situation so that it can be used fairly. You can’t just let developments run their course. Transparency is very important, so that everyone knows what is happening, but also has the opportunity to intervene and report if they notice that something is not right. That the press reports on it and that complaints are followed up.

In the case of drones, which are also used for remote sensing, there is already a larger social debate. There are fears of surveillance by drones. How justified is the concern in Germany? Is the regulation of drones in this country sufficient?

Drones that are no longer categorised as toys are actually quite heavily regulated in Germany. Right down to the fact that a “drone driver’s license,” i.e., certain proof of expertise, must be provided, and that drones are marked, so that you can find out who is responsible for a drone afterwards. In principle, it’s pretty clear what you’re allowed to do and what you’re not. Of course, you can’t let your drone look into other neighbours’ bedrooms or fly over gatherings – if only because a drone could crash. You are also not allowed to fly near airfields. So a lot of things are regulated, but I’m not sure if all drone pilots know the regulations as well as they should. So I don’t see so much need to tighten up in the law – it’s more about communicating it. There are also some ways to offer technical support to the regulations. For example, by immediately marking the areas that drones are not allowed to fly over, for example with geofencing. Technically, this would help us already overcome the first hurdle, because the programming of the drone could ensure that it does not fly into an airfield at all, for example.

Okay, so there are technical possibilities that would support the regulations. As I understand it, when it comes to German law, there is a sufficient basis for me to be able to say, for example: “This drone footage violates my privacy and I want it removed from the network.” Is that right?

In principle, yes, but here’s the problem: How do you determine that a recording ends up on the internet? Something flies by… And some drones you can hear, some less so. Is a camera even switched on, and if so, is it an automatic transmission – possibly to the internet? And what happens to it later? This means that the person responsible for the drone has to fulfill their legal responsibilities, but if they don’t, it’s hard to prove it or even track them down.

With satellites, that would be even more difficult, right? I can’t hear or see that a satellite is flying above me at a high altitude and maybe capturing images.

Right. You have to know that something like that has happened in the first place in order to take action against it. So it would be good to be able to get an overview here first. That’s why I think the idea of a kind of satellite register makes sense. For each of these flying objects, which are not visible to us, it would then be clear who is responsible. What national laws are in place? Do they have contact people? What is the satellite actually designed for? Is the purpose, for example, weather observation, are research data being collected? And what happens to the data? And what is the resolution of the images?

Of course, it’s possible that some countries wouldn’t agree to participate in something like that. And I think it is very likely that military satellites wouldn’t be included in a register like that. So there would still be gaps, but a registry like that would be a first step towards more awareness of satellite imagery….

Suppose I am aware that personal satellite data are being processed. How can I exercise my rights with regard to satellite images?

The data protection rights that citizens have also apply here in principle. In most cases, it is a question of weighing up which interests outweigh the others: What are the interests of the person taking the picture, who may also be processing it for commercial purposes or for the public good – and what about the rights and freedoms or the interests of those being photographed? I expect some court decisions on this in the future. In addition to the purposes, important points are, for example, the resolution of the data, whether a real-time analysis takes place, and to what extent the data are published.

Google Street View pixelates or blurs personal details in the images, e.g. images of faces or car licence plates. Would something like this also be an option for satellite images that show personal data?

Yes, there would certainly be technical possibilities. And it would also be possible to deliberately set or reduce the resolution of a satellite in such a way that, for example, no reference to a person can be made in the first place. Or, on the other hand, certain areas where there are no people, where a high resolution is not problematic in terms of data protection, they can be recorded more precisely – Antarctica for example.

What other ways could there be to create trust?

Knowing that thousands of satellites are flying overhead and that everyone could potentially be watching me can, of course, create fear or a feeling of powerlessness. However, if assurances are given here that independent auditing organisations have checked the parameters, that those responsible are looking into their cards and handling the data responsibly and correctly and protecting it effectively against misuse – if all this were disclosed, then that could also lead to more trust. The fact that some states are probably not interested in making their governmental or even their corporate satellites more transparent is another matter.

Germany has a satellite data security law. But the topic of satellites is an international one. Would such a law or a “satellite code” also be conceivable on a global level?

In my opinion, it would be very difficult, but I can imagine that many countries would initially support moving in that direction. Whether everyone then adheres to the law, would, of course, be another matter. But I wouldn’t give up on the idea because there are a few that are backing out. It can be good manners to be part of it, and it probably also shows a certain consensus on the rule of law. Even for states that don’t join initially, I wouldn’t give up hope for the future.

At the European level, when it comes to observations of individuals in the EU, that’s where the GDPR, the General Data Protection Regulation, comes into play. Providers outside of Europe are also obliged to comply with the DSGVO in these cases. Unfortunately, this does not always work out, and it is also very difficult to enforce.

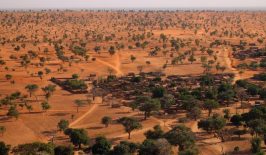

There are many cases where satellite data and drone imagery are used to highlight abuses. Such data can be used, for example, to detect oil spills or methane leaks, or to prevent rainforest deforestation or illegal fishing. But there are, of course, other use scenarios as well: The European border protection agency Frontex, for example, uses such data to track down boats of refugees in the Mediterranean Sea in order to “fend them off.” So to what extent do these applications harbour the risk of misuse in the wrong hands?

The potential is definitely there for such data to be used for good or bad. The data or the technology based on it is not neutral or objective at all, but can often be used in different directions.

An example would be the monitoring of elephants, which are tracked in ordert to protect them and their habitats. Wildlife protection is definitely an application that would be positive and definitely widely accepted. However, exactly the same can be applied to humans. For example, if habitats are destroyed, through war or climate change or environmental disasters, then this can result in large movements of people. But if the images are then deployed to strengthen measures to push people back who are migrating, then the whole thing flips: What was perfectly fine in the context of elephants suddenly becomes highly charged in terms of ethics and data protection.

Of course, the elephant example can also be turned around. A poacher could also track the elephant and use this to hunt the animals. So the same technology has very different consequences. It is important to note that. Just because there are invidual cases that are problematic, it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t use the technology at all. That’s not how it works. It’s difficult to solve issues like this, but there’s nothing against continuing to promote and use technologies like this for the greater good.

How can we ensure that that happens?

It is important to create an awareness of what is happening overall with the digitalisation of our society. Because digitalisation is leading to a shift in power. There is a lot of potential in the fact that we can participate and be effective together on the basis of certain data and captures. Such techniques and crowd effects, like citizen science, for example sightings of such satellite images by people for better environmental protection, can help to improve the world a bit.

On the other hand, however, guardrails must be put in place to prevent negative effects of the risks in the first place. In the case of satellites, the resolution could be limited or certain areas could be specially protected so that they are perhaps not visible at all. The important thing is that we have a handle on the risks and that there is awareness of them. And when the world changes, when technology changes, then the risks have to be reassessed and appropriate measures taken. In the area of data protection, we are making a contribution to this, but here we need even more involvement in impact assessment and for solution strategies.

I am not pessimistic about the way the world is developing, quite the opposite. But if we just let these developments run their course, if we don’t make ourselves aware of them, then we will end up with bigger problems. However, if we shape these developments, taking into account the possible consequences and risks, then I believe we can shape digitalisation for the better.

This article is part of the RESET Special Feature “Satellites for Sustainable Development”. Click here to explore all of the articles in the series.

This is a translation of an original article that first appeared on RESET’s German-language site.